a one act play by Isabel de Santa Rita Vas

(A mustard seed art company production)

Cast

Alice – Woman in her '60s; grief-stricken widow mourning the loss of her former life; given to histrionics and hallucinations.

Durijesh – Man in his '40s; grandson of Venkatesh the boatman, who used to bring coconuts from the bhatt to Alice's privileged family.

Premnath – Man in his '70s; the family goldsmith who always wore a spotless dhoti.

Marina – Woman in her 20s; the cook's daughter.

The setting

Late evening. The wreckage of an old house, facing a narrow, free-flowing river. Not far, a gulmohar tree in bloom, gulmohar flowers strewn around it, blown off by a gust of wind. Alice is walking around, observing the collapsed structure; she stands at the foot of the tree, examines the foliage, then sniffs at the blowing wind which threatens rain. She picks up a flower from the ground.

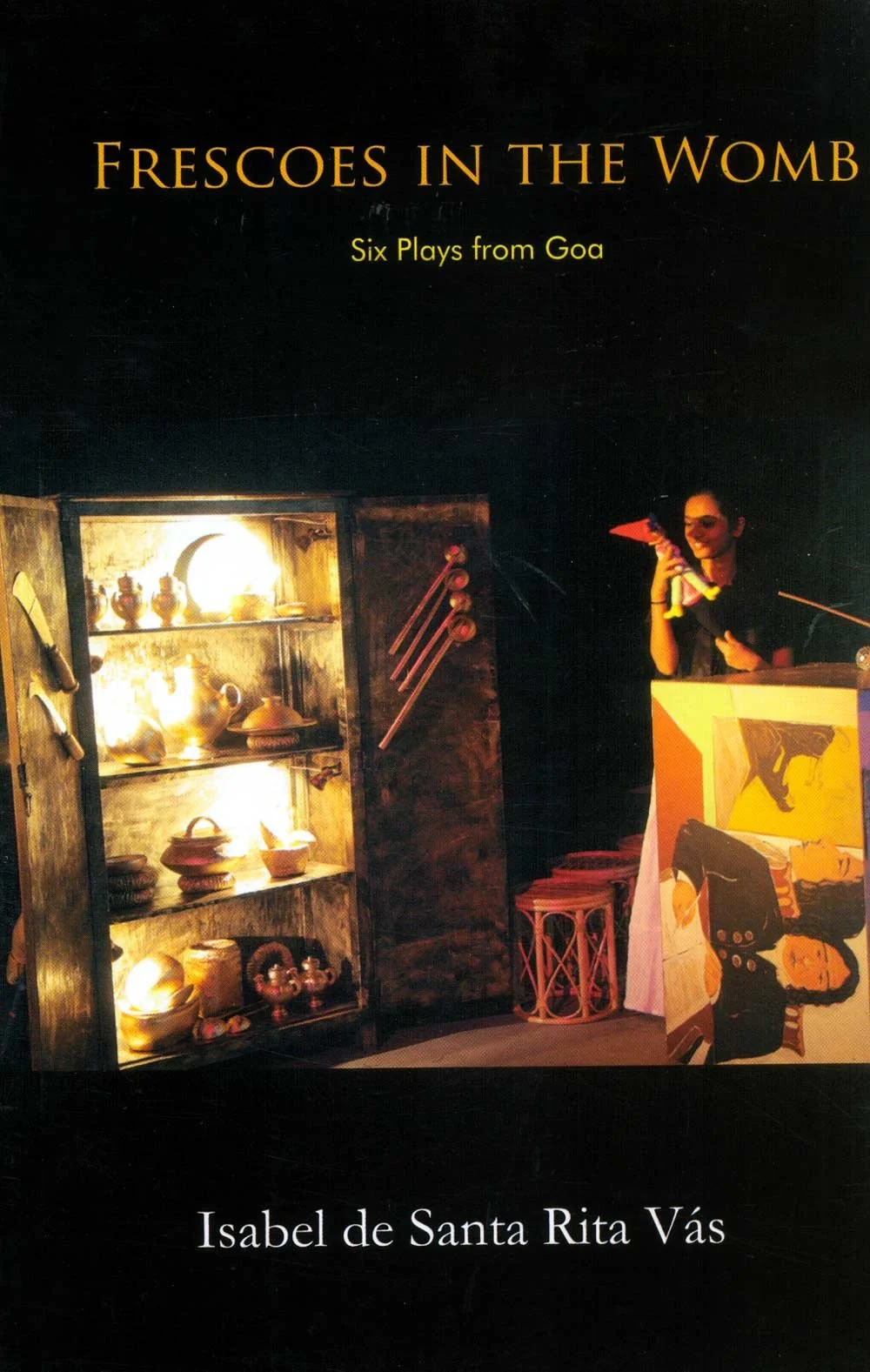

A performance of the play 'Voices Within Me' on 23 August 2014 at the Sanskruti Bhavan, Panjim, Goa.

ACT I

ALICE: Have you heard the silence when the music is over? The petals twist and tumble without a word, and rest on the ground. A moment of no-sound. (Goes back to the house.) But when these walls crumbled in the cyclone, what a crash it must’ve been! ( Examines the rubble.) To a bride this house was all the promises of marriage. Not majestic like my father’s mansion, but handsome and inviting. António, can’t the dead and the living touch hands in remembering? You can hear, me, surely? Be quiet, woman. Keep your imagination tied securely to the gulmohar tree. (Laughs.) Be logical, be practical. Imagining entices you down leafy pathways, but they’re crawling with red ants. (She is looking for something.) I wonder if it survived the wreckage. This morning I couldn’t start digging in the rubble, in the midst of the crowd, and those press fellows. Damn. Why didn’t I come for it before? Last night, as the gale burst in fury, all I could think of was the House-by-the-River. And my António-by-the-River. I could see you looking down from the clouds and muttering, “Arre baba, poddta mu-re, amchem ghor. Guelem, guelem…” Oooola-la, couldn’t you have asked the Good Lord up there to hold the cyclone back? Five days and the sale would be finalized. Now... Who wants to buy mud? (Stands quietly, weepy. Suddenly bursts out laughing uproariously.) Let it go. Vassimbor! I’ll find it, I’ll find it. Forgive, me, António. I’m crazy. But you’ve always known that. That’s why you forgave me. (Potters around, looking for something.) You did, didn’t you? (Enter Durijesh, carrying a thick coiled ropel.)

DURIJESH (He enters furtively, then crashes into Alice. Shouts): Ahhhhh! Deva Deva. Ah, sorry, sorry. Who are you?

ALICE: Who are you, man? Coming to my house without an invitation. Out!

DURIJESH: Your house?

ALICE: With a rope. (Looks suspiciously at the rope.) Come to hang yourself in a picturesque spot?

DURIJESH: Hang myself?

ALICE: ‘Young Man Hangs Himself near House by the River.’ You’ll make the front page. But only for a day, man. History comes and goes before you can say Christopher Columbus. Aya Ram, Gaya Ram. (Laughs.) Come to steal bits of my house or what? (Puts out her hand.) Welcome, Robber. (Durijesh shakes it before he realizes what he is doing.) I’ll keep an eye on what you steal.

DURIJESH: (Draws back his hand hastily.) Robber? I’ve only come to take what is my own.

ALICE (Laughs uproariously): Your ownu? Your own, let’s see. The gulmohar flowers, there’s nobody else around this time of the night, they’re yours. Take what is yours and go. I’ve got work here.

DURIJESH (Puzzled by her): Work?

ALICE: You’ve got a limited vocabulary.

DURIJESH: You’re mad or what?

ALICE: A bit of both.

DURIJESH: Both?

ALICE: Limited vocabulary. See, sometimes I’m mad. Sometimes I’m logical. Don’t repeat ‘logical’!

DURIJESH: You confuse me. (Alice laughs.) I’ll take the boat and go. Before the storm breaks.

ALICE: You confuse me. You came by boat? Down the river? Are you an image from my past? Or my future?

DURIJESH (Forcefully): Boat! From my past. Remember Venkatesh? I want his boat. If it’s spoilt or something, no problem, I know it’s 40 years. Bhau-saheb Bandodkar died on 12th August 1973. But it’s my grandfather’s boat, no? So I’ll buy it back. I can afford it.

ALICE: I give up. (She collapses on a makeshift seat. To herself.) All that medication, and I’m imagining people. Damn! But if he’s a creature of my own rambling, what have I to fear? (Speaks kindly to Durijesh, pats his arm lightly.) Listen, I know nothing about your boat. But sit and tell me.

DURIJESH: Maybe it’s your boat now. You paid money for it. (Tired, he sits.) But my grandfather made it. Venkatesh. And Swarna, that’s the name.

ALICE: Hey, I remember Venkatesh! Venkatesh would bring us coconuts from the bhatt, and red-and-green mangoes in May. Oooou-la-la, his hairstyle: a beautiful shenddi on a bald head. Tall and spare, your father.

DURIJESH: Grandfather. I am Durijesh. My father and mother were drowned when a canoe sank. Going to the Zatra. I was a small boy. Azo took care of me. Then he sold his boat. It wasn’t a big boat. Was it in the backyard here?

ALICE: Backyard here? Damn, my vocabulary’s getting limited.

DURIJESH: He must’ve walked, that evening. Then swum like an old desperate fish. The day Bhau died. He came home and died.

(Alice gets up, goes to Durijesh, shakes him by both shoulders.)

DURIJESH: What? Stop! It’s true, it’s true!

ALICE (Stares at him): Excuse me. (Pinches him on the arm. Durijesh shouts and jumps up, startled.)

DURIJESH: Ai!Ai! What’re you doing? You’re…

ALICE: Sorry. It proves nothing anyway. (Laughs.)

DURIJESH: You’re mad. Keep your hands away. You’re the lady of the house, no?

ALICE: Yes! I’m Alice Monteiro. Owner of these ruins. I was going to sell the house. History and memory. Treacherous coins, both.

DURIJESH: It was in the papers. Shocking! Blown down by last night’s cyclone, they said. On the side, a picture of the house while it was standing. I recognized it! This was the house! I started trembling, like a woman with malaria. Ha! (Irritated.) Too much talk, now. Waste of time! Uloit rau… Let me start searching. (He begins his search in a great frenzy.)

ALICE (Shouts): No! No! No! (Begins to struggle with Durijesh, pulling him away from the ruins.) You won’t grab my treasure. I don’t know how you could find out, but you don’t fool me. Stop this natak. (Hysterical.) I know why you’re here. I’ll call the police! (Durijesh stops abruptly. Alice keeps pulling at his arm and the rope coiled around it.) Never heard a more absurd story. I won’t let you take it away. I won’t! (She lets go suddenly, sinks to her knees.)

DURIJESH (Stands transfixed, then squats by her side.): It’s OK, Aunty. I don’t… (She interrupts him.)

ALICE: (Agitated) I’m not your aunty. I’m nobody’s aunty. (Quietens down.) I am somebody’s granny. But I’ve never heard the gift of that name. That’s why I must offer them some history. A teacup of history.

DURIJESH: Madam, what I want is useless to you. An old boat. You must’ve stored it away and forgotten. (A new thought.) Or sold? Deva, did you sell it? Tell me you’ve sold it and I’ll go. Tell me it’s under this mud and stones, and I’ll dig and dig with my hands, couldn’t bring a pickaxe. I’ll pay your price, get her home somehow, make her strong again.

ALICE: Heht! There’s no boat in my house!

DURIJESH: But … (At a loss.) How I know it’s your house, ge? Who are you? (Warming to his theme.) The owner of the house would be here in the middle of the night, or what? A woman alone, with a storm marching?

ALICE (To herself): The storms within the soul blow this woman around without a compass.

DURIJESH: Tell me!

ALICE: Alice was a bride, see? T’was a house full of people, all wise and wrinkled. In-laws to be propitiated like unknown gods. (Chuckles.) Silly Alice wanted to laugh and dance. She was eighteen. Overjoyed to be married. From lil’ Princess in her father’s home to Empress in her husband’s castle. (Laughs.) Silly Alice had to turn into dough in the hands of the women, to be kneaded into shape. (Softly.) But my António drew me close to his heart. “You’ll be mistress of the house one day, my dearest,” he’d whisper at night, kissing my tears away. “Your home, your family, soon.” (Sadly.) He was right. António was always right. They all died one day.

DURIJESH (Shocked): They all died one day?

ALICE (Does not understand. Then laughs uproariously): Not all on the same day. Eventually. Made room for me to get some fancy clothes tailored and go visiting all the fancy relatives. (Looks at him intently.) “Heartless bitch,” that’s what you’re thinking, no? (Moves close to Durijesh.) No, António. Who plans something as stupid as falling in love? It just… happened. You know, the way running water fills a hollow in the ground. We’d laugh together. Raúl. I hardly saw you those days, Tónio. Deathly hands over my throat kept telling me I was cold… and old. Raúl would touch my face, it would stir fire in my loins. But nothing happened, I swear. Nothing. He was your cousin; I was…silly. I didn’t… betray you. You never said a word. Why did you close yourself from me? (Touches Durijesh’s face. He freezes.) Even when you made love to me. You did forgive me? Tónio? (Sits on Durijesh’s lap. He pushes her away and jumps up.)

DURIJESH: Leave me alone! You’re… you’re…

ALICE: Who are you?

DURIJESH: Durijesh. I’ve come for 'Swarna'.

ALICE: For all I know you’re not even here.

DURIJESH: For all I know you are just a… I don’t understand. And I don’t believe your crazy tales.

ALICE: Two shadows suspicious of each other’s substance. (Takes a few steps with an effort.) You may be – all in my head. No? Well, I’ll make you believe my stories. And why should I believe you?

DURIJESH: Please, you remembered my Azoba.

ALICE: Memories are liars, defectors and traitors. Stories make them real.

DURIJESH: I… don’t understand.

ALICE: No, how would you? You’ve never thrashed around night after sleepless night imagining and hating and yearning? No. You’ve never been medicated for depression.

DURIJESH: (Restless): How to convince you? (Speaks slowly and firmly as if to a child.) Bai ge, I’m Venkatesh’s grandson. I’m Durijesh. I want to buy the boat.

ALICE: Names, names.

DURIJESH (Stands and paces and the words tumble out in desperation): Venkateshbhai and Durgabai, Azo ani Aaji. Everyone knew them. The most hardworking people old people. I can hear Aaji pushing open the door of the hut, thrrrrr… even before the animals woke up. She went out for water, walked with two pots to a well so many miles away. When I was little, I was a third pot, on her hip. Azo did everything: he chopped wood, tended the goats, Kamala and Mangala, he went fishing, plucked coconuts. What he did best was to row the boat, his Swarna, carrying paddy and coconuts for the bhattcan in the city. For you.

ALICE: For my mother-in-law.

DURIJESH (Angrily): You did not have rice and curry? And eat it with no knowledge? We’d set out before the dawn even began to yawn and stretch. Azo would take gigantic strides and I would skip a step and run run, skip and run run, in pure silence, only our breath and feet praying to the morning. At the riverside Azo would pull out Swarna, pick me up and stand me up at the bottom, as she rocked gently. (Chuckles.) She smelt better than Aaji. Ah, smelt of tar and salt. We’d sail away into the river, into the ocean, into the sky. Azoba, Swarna and me.

ALICE: This proves… nothing. Could be anybody’s tale.

DURIJESH (Not listening.): Sometimes goldsmith Premnath would come with us to the city. He’d bring soft chapattis to eat on the way, and some pez in a round white pot with a blue cover. Premnath Shett spoke smooth words, like river pebbles. He asked me once what I wanted to do in life. I hid behind my Azoba’s kashtti.

ALICE: Premnath Lotlikar was the family goldsmith. He wore a spotless dhoti, a black coat and a black topi. Natty dude, you might say.

DURIJESH: Azo would tie Swarna by the river-front, up there. I’d help lift the bags, Azo would carry them on his head, up the back steps. I’d run after him. There would be small yellow chickens running all over the kitchen. (Enter Premnath, dressed in white dhoti, white shirt with a black coat over it. On his head a black topi. Durijesh is overjoyed.) Premnathbhai! Imagine! We were remembering you.

ALICE: Someone I haven’t seen for years! Mr. Lotlikar, are you well? (She extends a hand but Premnath offers a namaskar.)

PREMNATH: Namaskar. Bori asai ki nam? Bab kosso assa?

ALICE: Ah… My husband passed away years ago. António was a great admirer of your artistry.

PREMNATH: Antonbab had a fine taste in jewellery. The ladies always asked for his opinion, hahn? When it came to intricate patterns.

DURIJESH (Touches Premnath’s feet.): Namaskar, Shett-bab. So happy to meet my grandfather’s friend.

PREMNATH: I’ve believed in living my life as everybody’s friend, hahn?

DURIJESH: I’m Durijesh, the boatman’s grandson.

ALICE: Poor boy! His imagination spins madly in a cyclone. Claims you travelled in Venkatesh’s canoe. Naaa. You were always one for the good things of life, Mr. Lotlikar. You came by launch and then took a horse-carriage. In a canoe? Damn it, you carried gold ornaments in your pocket.

DURIJESH: Shettji did come with us. I can still taste the chapattis with ghee.

ALICE: (Laughs): Chapattis with ghee! What else?

DURIJESH: Mango chutney.

PREMNATH: Venkatesh. From my village. Well, almost. It’s a separate little waddo, but who cares. You’re Venkatesh’s boy, yes. He came to consult me when he needed advice.

DURIJESH: Azo told me, you came to our hut with lots of gold two days before Liberation.

ALICE: Imagination!

DURIJESH: You said, “Can you take good care of my gold sovereigns? And some jewellery sets?” Azo tied everything in thick cloth and buried it in the ground. Not far from the grinding stone. After all the noise of the armies was over he went to your house with every bit of gold in place. He was so proud of that.

PREMNATH: I paid him!

DURIJESH: Yes, you paid him. How much?

PREMNATH (Angry): After all these years, you expect me to remember? (Durijesh moves away.)

ALICE: Ah yes, Liberation day! People think it was a surprise when it came but…

PREMNATH: …but we all knew, hahn? We could hide our valuables. Who knows what can happen in war, how long it lasts and what terror can strike, hanh?

ALICE: We were lucky. It was all over in four days.

DURIJESH (From a distance): Pity, I was not born yet. Azo had gone to Mapusa with vegetables, suddenly he began to hear strange noises in the sky, then people running. He forgot his basket and ran. Halfway home he heard a big explosion. The whole earth shook. Azo fell down. He picked himself up and ran all the way home. That night he heard that the bridge in Mapusa had been blasted off. But God brought my Azoba home. Next day there were soldiers passing through our village. One of them entered our hut and took away our nice transistor radio.

PREMNATH: The cyclone did this? A beautiful verandah facing the river… I’m sad for your family, hanh?

ALICE: Beautiful verandah. The children would love to run around, we’d watch the changing moods of this river of ours. All gone. My daughter Marie-Lou married and went to Bombay. She died of kidney complications years ago. Gone.

PREMNATH: Such a good family…

ALICE: When my son Anil’s problems started in Africa, it was… too much. António had a stroke. He collapsed suddenly. An empty house full of dark corners? Naaah. I moved. Am selling this one. Deal was to have been signed in another five days. Now… (Shrugs.)

DURIJESH (From a distance): What about Swarna?

ALICE: Go away, you chor!

DURIJESH (Rushes upon her, barks into her face): I’m no chor! I’ve taken nothing from no one. (To Premnath:) I must find Swarna. (To Alice, tearful:) Can I start digging? If the storm breaks, we’re lost, please!

PREMNATH: Deva, Deva, a lady died here? Buried under the stones, hanh?

ALICE (Scornfully): Nobody died. House was empty. (Alice walks off. Thunder and lightning. Alice rummages in the rubble, humming to herself.)

DURIJESH (To Premnath): You’ve come for the necklace? I’ll help you look. Quickly. It’s going to rain. It poured when Azoba died. It was August, too, that year. He loaded the wood in the boat. We never saw Swarna again. (Alice jumps up with a shout. Then she goes back to her searching.)

PREMNATH: Poor woman. All this has been too much for her, hahn?

DURIJESH: No. She was born cracked. (Confidentially.) If the jewellery is in a velvet box, difficult to find in this mountain of rubbish, no?

PREMNATH: A diviner can smell springs of water, a shett can smell gold in a pigsty. (Laughs.) I’ll go look around. (He moves away, exploring. Suddenly Alice is dancing and singing and clutching something to her chest.)

ALICE: (She sings loudly:)

Marina, Marina, Marina

Ti voglio al piu' presto sposar

Marina, Marina, Marina

Ti voglio al piu' presto sposar

O mia bella mora

No non mi lasciare

Non mi devi rovinare

Oh, no, no, no, no, no (She is holding a small metal box.) Can you see it?

DURIJESH: Shett-bab’s fator necklace?

ALICE: You were born cracked.

DURIJESH: Premnath-bhai told Azoba all about that gold-and-fator set. He sold it to you at a discount because you promised to lend it to his wife. For their daughter’s marriage, it was. But you never gave it! They had to hear lots of talk from all the ladies, because the Shett’s wife did not wear a new necklace for her own daughter’s wedding. What I hear, I remember!

ALICE: What utter rot! We did have a malachite stone set made for my mother-in-law. On her golden wedding anniversary. We paid good money for it, baba. But lend, what talk of lending is that? Inventing shitty tales! An idiot’s mind can cook up any reality. Hey, what unusual shape did the pendant have? Tell me or shut up. (Durijesh looks exasperated. Premnath has approached them. She sings.) Marina, Marina, Marina. (She takes shelter under the gulmohar tree.)

PREMNATH: Gold. So important, hahn? You have no gold, you’re dung. My greatest mistake was to hand over my money to politicians. That scoundrel met me at my daughter’s marriage. My third daughter, Kritika. He took me aside, like a friend. “You must invest in this mine,” he whispered, “it’s like a gold mine. Few people know about it. The profits will be more than one thousand per cent!” I believed, hahn? “The party will also benefit, we must sacrifice for the party,” he proclaimed. I sold my gold. I invested. Five daughters to get settled, see? It was a mine that failed. I failed, hahn? He knew, all the time. Tajer padd poddun. So, no money to get my Shreenidhi married… Dying without doing my duty, can I rest in peace? (Marina appears. All are astonished.) Who are you?

MARINA: Hi, I’m Marina.

PREMNATH: Marina? Strange, hahn? As in her song?

MARINA: Absolutely!

ALICE: Welcome, Marina. I was just thinking of Vicente. Creative guy, though he was only a cook. (Laughs.) I rather liked the chap. You’re his daughter, I presume?

MARINA: You presume right, ma’am. Come looking for my Pop’s notebooks. (Examines the rubble.)

ALICE: Come this way. The storm might break anytime!

MARINA : You know rain doesn’t touch me. So, bring me up to speed on what’s up here. Why’s everyone looking so glum? (Hums:) Marina, Marina, Marina. You liked my Pop? Below-the-belt-stuff between you guys?

ALICE: Naaah… You Gen-Next blokes can never think above the belt or what? What we had between us was… kinda-above-the-neck-stuff.

MARINA: Vicente-Only-a-Cook had creative beans in his bread-basket?

ALICE: Tell me about it!

MARINA: You tell me about it. He wrote short stories? Tiatr scripts? By candle light in the maddo? That what you tell me? Rattle off, girl, we’ve got us an audience. (Takes out a notebook and pen from her bag.)

PREMNATH: You two are friends, hahn? (To Marina) You’re from…?

MARINA: The lady and I meet whenever Vicente-the-Cook sings us together.

DURIJESH: Saba bogos, I can’t understand anything. My head is aching terribly. Crazy, it’s raining, but the headache’s not going away only.

PREMNATH: Rain cures your headaches? (ALICE and MARINA laugh.) No, no, listen, this boy would know things we don’t dream of. His grandfather had a bond with… everything. We inherit more than houses, hahn?

MARINA: Oh yeah, genes, DNA, nuclear transcript… we journalists read about such things. Makes my head, like, spin. Give me short stories and stuff, anytime. Cool. What did Pop write about, anyways?

ALICE: I attended one of his tiatrs. It was sweet, tragedy dressed as comedy. Me, I too wished I could write, but see, I went and became a teacher. Vicente wrote. “How can you sing and write at the same time?” I asked him. “My mother sang even as I was being born, so how can I help it?” he said. (Marina scribbles.)

PREMNATH: And he sang Marina, Marina?

ALICE: It’s an Italian love song. But here’s Vicente after too many glasses of feni:

Marina, Marina, Marina

Minister magta tis hazar

Marina, Marina, Marina

Tum taka munn ‘tum re zog mar!’

MARINA: Cool dude, squatting in that loft. Bent over his notebook, licking the lead of his pencil, scribbling like there’s no tomorrow. His work must have value now. Like, sentimental value, and hey, literary value, you know? What a scoop, wow!

PREMNATH: Is that all you want, you shameless girl? Hanh?

MARINA: No, lover boy. Heard of justice, anytime?

DURIJESH: Why didn’t he come, your Pappa? He just left his writings somewhere? His papers will be soaked by now. Deva, Deva.

MARINA: He… got caught in a brawl in a tavern. A friend hit him on the head - with a koito. They brought him home, dead. Years ago. Vicente Cunha, writer of plays and stories. His famous tiatr in the village was about the Opinion Poll, yaar. It was called ‘Mot Mar, Zog Mar’. Big hit, yaar, ran for over a hundred shows.

DURIJESH: What is the Opinear Goal? A game, like? (Alice and Premnath howl.)

MARINA: Yes, a game of politics. Dayanand Bandodkar and his team versus Jack Sequeira, Uday Bhembre and their team. Fuloi!

DURIJESH (Jumps up): Bhau-saheb Bandodkar! He’d promised to help Azo to buy the land on which we live. A god, Bhau-saheb!

ALICE: Happily this god failed. Or we might have had a different history.

DURIJESH: Bhau-saheb would’ve given us our land.

PREMNATH: Then our land would become another land.

MARINA: Pop was fascinated with the Opinion Poll. Full-blownWar between the Red Flower and the Two Green Leaves! “Tujem mot fokot Don Panar! ”, he would shout. When the counting of the referendum votes was going on, he and his friends carried feni bottles in their pockets, but they completely forgot to drink! Fuloi! The results were like winning the Nobel Prize or something. Like Vicente Cunha had saved Planet Earth in Star Wars.

DURIJESH: What results, go? Who scored? Bhau-saheb?

MARINA (Shakes her head): Goa remained a separate Union Territory. Not merged with our huge Maharashtrian neighbor. Pop’s history book was complete.

DURIJESH: History-bistory is not my cup of tea. But I know Azoba had an appointment to meet Bhau-saheb. He never went.

PREMNATH: Never went?

DURIJESH: See, I wanted to go to Pune to study. Where was the money? Aaji would give only me hard words. “Work like everybody else”, she shouted. But was I everybody else? I was Durijesh, the dreamer. So that day, Azo took the boat out and a load of firewood and came to the City. He was late coming home, very late. I walked all night by the river, but no boat. Then at dawn, Azo came walking home, dragging himself through the pouring rain. He fell on the doorstep. He would not eat or drink. He only said over and over again, “I killed Bhau-saheb”. “I sold Swarna and I killed Bhau-saheb.”

ALICE: Dayanand Bandodkar was a hugely popular Chief Minister. He died in 1973. (To Durijesh) He was sixty-two years old!

MARINA: He sold his boat? Who knows, he heard of Bhau’s death and his feverish brain told him he had contributed to it.

DURIJESH: His hands were fists as he lay dying. When they were washing the body, they found money in his hands. From the sale of the boat. My Azo’s great sin. I hated Azo for throwing us into a dark well. I took the money and ran, far away. I wasted it all. (Quietly.) I’m back now. Aaji is old. My business can support us, a small fishing enterprise. I’m back.

ALICE (Draws Dirijesh to shelter): Come to the shelter of the tree. Nobody killed your Azoba’s Bhau. You mad or something?

DURIJESH : (Softly) Both. (They stand together under the tree.)

PREMNATH: We hanker after legacies. Voices for our children. But they have their own voices, hahn? (Thunder and lightning.)

ALICE: My only son went away from us to Africa. He got into politics, ran into trouble, big trouble. We thought him dead. Then one day we received a call for ransom, he was held captive… but alive. António rushed to sell his mother’s malachite jewelry and Anil was set free. He’s never come home. Until now. Anil is coming home next week with his children. For a holiday. My son Anil. My grand-daughter. My grandson.

PREMNATH: Sure? They’re not like me or something? People who have lived - and gone?

MARINA: Or like me? People who never were? And never will be?

PREMNATH (Understands): You wished Marina here, she came. This boy had need of me. I came. Anil… and his children…

DURIJESH (To Premnath): You are…?

PREMNATH (Smiles): No, I was.

DURIJESH (To Marina): You are…?

MARINA (Smiles): No, I never was.

DURIJESH (shocked): You are…

PREMNATH: No, I was… (Durijesh turns to look at Marina.)

MARINA: Vicente never had any children.

ALICE: I’ll tie my imaginings to the Gulmohar tree. I’ll secure them. I’m practical and logical. (She mimes tying a dog to the tree.) Sit! (She pulls out an envelope from her bag and hands it to Durijesh. Forcefully.) Anil is arriving on Tuesday, flight no. C- 806, British Airways. His children Sophia and Anthony are 12 and 10 years old. I wanted a gift for them. (Shows what she has found in the ruins.) A portrait of their grandfather. I found it! (Moves forward with Durijesh whereas Premanath and Marina move into the background.) Something told me it would survive, this is an ancient mud-house. Metal box’s all flattened, but here’s my António. Miniature, set in gold filigree. The work of a famous artist from Venice… who... who… Ah, who cares? So handsome!

DURIJESH (Points at the moon): My name means ‘moon’. Swarna must be on the river, somewhere. I think Azo would’ve sold his boat to a fisherman.

MARINA: Pop’s favorit-est song was…

PREMNATH: Marina, Marina, Marina!

MARINA: Naaa... The Opinion Poll song! Ulhas Buyao’s masterpiece! Under the moonlight. Chandneachea Rati, maddachea savlent sarailya sobit manddar, Hatant ghalun hath nachumya gavumya ghumtachea modur tallar. (Background music continues for a few seconds, fades, a moment of total silence).

ALICE: Have you heard the silence when the song is over? Perfect. A touch of eternity. (A small silence. She stands by Durijesh, showing him the jewel. Premnath and Marina move further into the background, fading away.)

MARINA (Amiably): Hey… why didn’t you preserve his notebooks?! That’d have been so cool! (Sings)

Alice-bai, Alice-bai, Alice-bai

Tin Noman Morie kor tum rozar.

Bangarak koria ami bye-bye

Vicent-bab god’tolo cantar.

Isabel de Santa Rita Vas is a former lecturer in English at the Dhempe College of Arts and Science, Miramar, Goa, and at present on the guest faculty of Goa University. She is the founder member of the Mustard Seed Art Company formed in 1987, and the author of Frescoes in the Womb: Six Plays from Goa (Broadway; 2012). She has written over 35 plays in English. Voices After Me was first staged in July 2014 for Prayog Saanj, a theatre initiative of the Director of Art and Culture, Goa.

Frescoes in the Womb can be purchased here.