By Rochelle Potkar

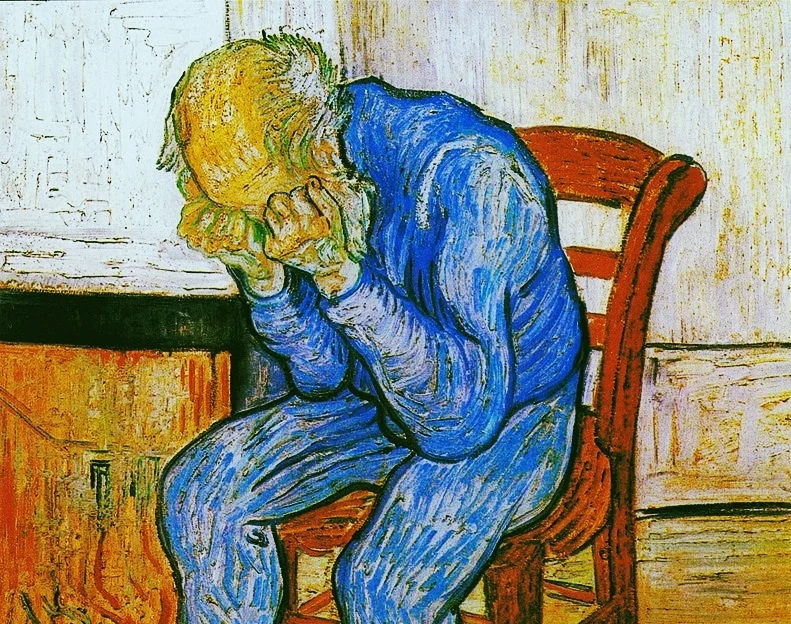

Joe Pereira sat in his cane chair every evening as mosquitoes crowded his head.

Buzz buzz.

‘Tcha!’ with a sweep of his hand.

Children ran screaming round and round in the compound.

‘Catch me! Aaah! No!’

‘Shut up all of you. Spoilt the peace of my life,’ screamed Joe in a quivering voice.

‘Get down from that gate,’ he said, standing up on his first floor verandah.

‘Swinging on it like it was a swing. I will complain to the secretary.’

His voice went hoarse with phlegm and then mute.

He sat down, only to be provoked this time by coconut gatherers.

‘Who asked you to climb the tree? Robbers! Not one coconut left on the tree. Take it to the market and sell it for two-two rupees.

Thieves! They’re worth much more. Papa had planted them.’

The children’s screaming, Joe’s screaming and the coconut gatherers’ laughter blend to make the evening a pleasant, noisy, happening one — the usual for passers-by and brisk walkers on the street, in front of the old bungalow on West Avenue.

A large resounding tap on the main door, and Joe rushes to answer it as echoes of his footsteps follow him. Mrs Clair would send him subsidised food in a hot case for 200 rupees a month. Joe would eat half of it in the night — curry and bread — and the other half in the afternoon — curry and rice. For breakfast, it was always a pav and a cup of tea made with milk powder.

Next, came the pavwala. Tap tap.

There was no maid to open the door. Joe had asked her to leave after she had opened the door to sweaty men who came into the house and took furniture and crockery down and out through the basement gate, that stood at the centre of the bungalow like a yawn.

The men gave her 50 rupees for fine bone chinaware, 500 rupees for the rosewood curio cupboard, and 1000 rupees for the teakwood wardrobe, a blue oxidized chain lamp and a bottle with a ship in it bought from Cyprus.

Joe had screamed over their backs, ‘This is my house. Get out or I will call the police.’

The men left through the unsteady, folding gate, leaving greasy fingerprints on the dust-smoothened railing.

The maid left soon after. She took with her six wine glasses wrapped in newspaper, two ivory-carved photo frames and figurines of the Mother of God.

Read the full story in our print anthology ‘The Brave New World of Goan Writing 2018.’ Buy the anthology here.

Rochelle Potkar is the author of The Arithmetic of Breasts and Other Stories (fiction) and Four Degrees of Separation (poetry). She is an alumna of Iowa’s International Writing Program and the Charles Wallace Writer’s Fellowship, Stirling. Paper Asylum (Copper Coin Publishing, May 2018) is her latest book publication. Some of her works have won awards, most recently, her poem ‘To Daraza’ won the Norton Girault Literary Prize 2018.