Clifford J. Pereira FRGS is an independent researcher, curator and museum consultant. His research in London, Vancouver and Hong Kong over the last sixteen years has focused on a variety of themes, leading to publications by UNESCO, BRILL and Routledge. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG); a research with the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Canada, and a guest lecturer with the African Studies Department, University of Hong Kong. His recent research into Canada's naval history was featured on CTV Halifax.

The In-Between World of Vikram Lall (Double Day Canada; 2003) can be purchased here.

By Clifford J. Pereira

Reading M.G. Vassanji’s The In-Between World of Vikram Lall (Double Day Canada; 2003), narrated by the eponymous Lall, a third-generation Indian-Kenyan, was no easy feat. The book required some focus and perseverance, and my dedication to finishing it has as much to do with my interest in the familiar narrative of East African Asian family histories as it is to do with Vassanji’s skill in weaving the story of an entire group of peoples into the twentieth century history of Kenya.

As an East African Asian and a Kenyan one too, I found all of the references well researched and the detail to colonial place names and language measured up to my own scrutiny formed of decades of historical research, field trips and childhood memories. But as a person of Goan origin, I had to question some of the references made to Goans in this book.

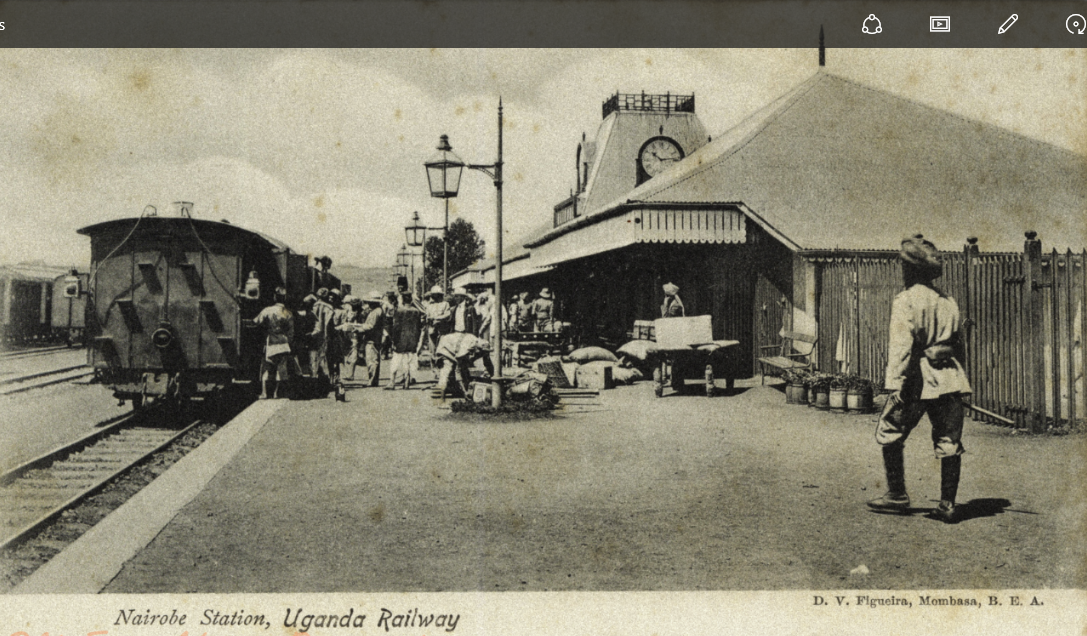

Goans appear to have only a fleeting mention in The In-Between World of Vikram Lall. Almost half of the book consists of Vikram Lall reminiscing of his days in 1950s colonial Nakuru in the heart of the Rift Valley. There are flash-backs to the founding of towns along the railway line by indentured Punjabi workers at the turn of the century. But Vassanji was either unaware or chose to exclude the presence of Goans in the Rift Valley dating back to 1899.

Nakuru, Kenya is where Vassanji's novel 'The In-between World of Vikram Lall' is set . The character Uncle Mahesh might have been modelled on the life of Eddie Pereira, who moved to Nakuru in 1950 and lived there during the Mau Mau insurgency. Nakuru was an important railway junction town and also capital of the White Highlands. Photo Courtesy Wikipedia.

Goans are particularly scarce in East African fiction from the colonial era. However there are many academic works in journals, all sorts of government publications (from Kenya, Uganda and Britain), newspapers and of course memoirs which Vassanji could have referred to. In fact, Goans make their non-fiction debut as “Goanese” in Richard Burton’s The Lake Regions of Central Africa (1860), followed by Harry Johnston’s The Uganda Protectorate (1902). The famous Out of Africa (1937) memoir by Danish Baroness Karen Blixen Finecke mentions South Asians, and devotes a chapter to the Sikh blacksmith Pooran Singh, but fails to make any mention of the Goan waiters she would have encountered at the Norfolk Hotel, at the railway station, at shops or perhaps as her doctor in pre-First World War Nairobi. Yet their presence is firmly confirmed by Errol Trzebinski in The Kenya Pioneers (1988). In fact Trzebinski devotes a whole chapter to the zebra-riding Dr. Rosendo Ribeiro. Apart from these memoirs, Vassanji did have at his disposal many other non-fiction publications by Europeans in independent Kenya that mention Kenya’s Goans such as To My Wife – Fifty Camels (1966) by Alyce Reece, Cynthia Salvadori’s fantastic study Through Open Doors (1983) and We Came in Dhows (1996). Not to mention those publications and memoirs authored by East African Goans such as Ladis Da Silva’s The Americanization of Goans (1976) or Mervyn Maciel’s wonderful book Bwana Karani (1985) and of course Teresa Albuquerque’s Goans of Kenya (1999).

Vassanji places the growth and subsequent crushing of the Mau Mau by the British, against everyday multi-racial contacts and constructs as seen by a child in 1950s small town Nakuru. At the time, Nakuru had a Goan population of around 200. But the character Vikram Lall's only Goan encounter makes its debut at the railway station (the EAR&H) in the form of a man called Tembo, which is Kiswahili for Elephant. Vassanji describes him:

“He was a Goan, brown as cinnamon, and was called Tembo to mock his extreme thinness.”

This “Tembo the Fireman, teeth gleaming like pearls” was working under a Sikh Engineer. This encounter is surprising as even in pre-independence Kenya records suggest that the fireman was rarely an Asian and commonly an African. Similarly Goans working in the railways at that time were mostly attached to the buffet cars, or employed as waiters, pursers and administrative clerks. So this brown “Tembo” is some what of a revelation and perhaps suggestive more of Vassanji’s own colour consciousness, based within the Indian sub-continent’s attitudes to colour and caste, than it is to do with artistic licence.

For much of the book, Goans disappear from the colourful and dramatic world of Vikram Lall, as if they were never there in East Africa. South Asians in East and Central Africa comprised less than 5% of the total population of the region in the period 1955-1960 and within that minority Goans only comprised 4%. Numerically East African Goans were a minority within a minority. But on the political stage Goan representation in the movements for independence in Eastern Africa was active and visible despite being a small minority.

I therefore found it curious that Vassanji chose to place The In-Between World of Vikram Lall in the Hindu-Punjabi community. Lateral thinking - perhaps the connections are not based on the actual community representation but on particular characters. After all, most good historical novelists of a realist tradition base their storyline and characters on well researched people that actually exist or existed, and whom they may have encountered, or for whom they have strong archival material. I base this on two novels: The Redundancy of Courage by Timothy Moand nominated for the Man Booker Prize (1991), set in the fictional country Danu in Southeast Asia, instantly recognisable as the former Portuguese colony of East Timor. The life story of Adolph Ng is recounted so clearly, as to be based on Mo himself or at the least a close friend. The other book is a translation by Karin Speedy from French, of Georges Baudoux’s Jean M ‘baraï - The Trepang Fisherman which was first published in the late nineteenth century, and set in the Southwest Pacific. Baudoux’s characters are actually based on his own experiences with the people he encountered in New Caledonia.

What has this to do with The In-Between World of Vikram Lall? It appears that Vassanji did capture the essense of something instantly recognisable to him. Nakuru had a very well organised Surati Gujarati community in the 1950s, and there was a connection between this Hindu community and the Goans, in the form of Eddie Sadashiva Pereira, a Mombasa-born Goan who was educated in British India and returned to Africa in the 1930s as an Indian nationalist. Pereira became Secretary General of the Indian Association in Nakuru and as he stated “I had written over 100 articles in the press against British and colonial rule in Kenya”. Pereira was imprisoned by the colonial authorities and despised by the settlers in the Rift Valley. In Vassanji’s novel there are echoes of Eddie Sadashiva Pereira in the guise of Mahesh Uncle, the quarrelsome Indian-educated uncle who wore homespun “khadi” cotton pyjama. The similarities are obvious. Pereira and the fictional Mahesh Uncle had sympathies for the Land and Freedom Movement – the Mau Mau; both characters were detested by the white settlers. On one occasion Mahesh Uncle is called a “Bengallee bastard” perhaps a reference to Bengali nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose.

Most importantly these two people – one a Goan who identified as an Indian and Kenyan nationalist, and the other a fictional character, lived in1950s Nakuru and are ridiculed, and ostracised by their own communities for their views. Vassanji locates Mahesh Uncle in the Hindu Punjabi community, one which like the Goans is a minority within a minority and also connected to the railways. Vasssanji brings out the same community fears of indigenous nationalist movements experienced by the Goans in Kenya. Fears enforced by a well organised imperial propaganda campaign backed by the settlers and the British Army. Vassanji describes the community and family rifts that this exposes. The schism between those for whom Kenya has become their only home even though they are assimilated into a hierarchical structure which is apartheid in every aspect but name, and those who have the privilege, luck or determination to be educated across the ocean in an India that has freed itself from imperialism and similar structures based on race. Perhaps Vassanji was thinking of Eddie Sadashiva Pereira, Pio Gama Pinto, Joseph Murumbi and Makhan Singh. This was a community divided between those who knew only of what they had as bad as it was and who made the best of it, against those who knew the possibilities of what it could be and aspired for those ideals.

Vassanji also explores the post-colonial challenges for the South Asian community as their hopes evaporated under Africanisation, corruption and violence. This is, as many authors of diverse hues will tell you not fiction. In The In-Between World of Vikram Lall, Goans reappear in post-colonial Kenya in the form a “Goan band playing Jazz” at a beach hotel at Mombasa. For Vikram Lall’s next encounter with the Goan community, Vassanji chooses Nairobi railway station where a Mr. Eddie Carvalho receives “a couple of slaps” from an African politician for asking his African assistant to wipe the engine in what Vassanji calls “a rather rude and foolish mannerism, reminiscent of arrogant colonial attitudes”. Is there any significance in the choice of ethnicity for this character? Why did Vassanji chose a Goan to embody ‘arrogant colonial attitudes’? One who mimics the mannerisms of the colonial masters, even after they have been kicked out. Vassanji may have considered the English-speaking East African Goan as a post colonial Asian enigma – the South Asian who forgot who he was after four hundred and fifty years of colonial rule. Vassanji was writing this at a time when Konkani was barely spoken in East Africa and whereGoans spoke English at home and at work

Later in the book Vikram Lall raises the issue of Kenya’s list of assassinations during the life-long term of Jomo Kenyatta and reinforces a popular perception that the Kenyatta Government and its clan-focussed Kikuyu faction was behind “the assassination of Pio Gama Pinto, a Marxist activist”. Later Vassanji tones down this description when he mentions “the Socialist, Gama Pinto”. It is almost as if Vassanji, himself an East African Asian, wants to steer away from the politics of the region - perhaps a wise move.

Given their socio-political role as Portuguese subjects in British or German East Africa, poised between the European coloniser and the colonised African, in many ways Kenyan Goans or all East African Goans would make for an interesting Vassanji book, perhaps entitled “The In-Between world of East African Goans”.