By Selma Carvalho

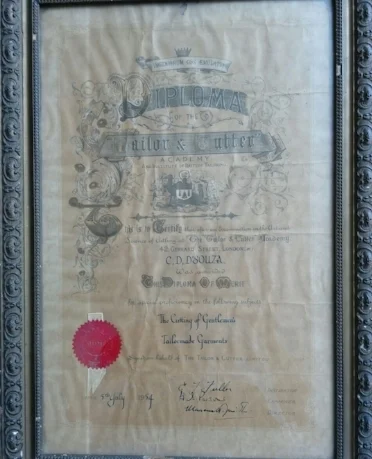

Recent surfacing of diploma certificates awarded in Portugal and this one in England, show that Goan tailors apart from a long apprenticeship also underwent more formal training. This diploma is awarded to C. D. D'Souza from the Tailor and Cutter Academy and Institute of British Tailoring, London in 1954. Photo courtesy by grandson Peter A D'Souza who carries on the family occupation running a high-end outlet in Ahmedabad.

Sabby Mendes, a tailor, is the fictional hero of Maria Lynch’s book Beneath the African Sun (FriensenPress; 2015), who as a eighteen year old travels to East Africa, to ply his trade.

At the opening of the twentieth century, a veritable exodus of Goan clerks travelled to British East Africa to find employment in the colonial administration. But a wave of working class Goans – cooks, stewards, tailors, carpenters and petty shopkeepers – had preceded them initially to Zanzibar and then to Mombasa and as deep into the interior as the Shire valley, better known today as Malawi.

It is now near impossible to cast a forensic eye on the lives of the working poor. Any documentary evidence left behind by way of letters has never been collected and archived. As such we have to rely on other methods, namely story telling and oral histories to piece together a narrative which tells the subaltern story. Beneath the African Sun sets out to do that.

For a book which starts by stating, ‘the larger events that form the backdrop of the novel are drawn from historical fact,’ it begins with a historical aberration. Sabby Mendes in 1916 embarks on a four week journey by dhow from Goa to Mombasa. Historically speaking, Goans would have made that journey from Bombay as that is where trade dhows set out for Africa. There were dhows plying from Gujarat too, but the other port from which Goans would have left by dhow was Karachi. By then, a fair number of Goans had settled in that lucrative port city, and when East Africa opened up, they made their way to these newly founded frontier townships.

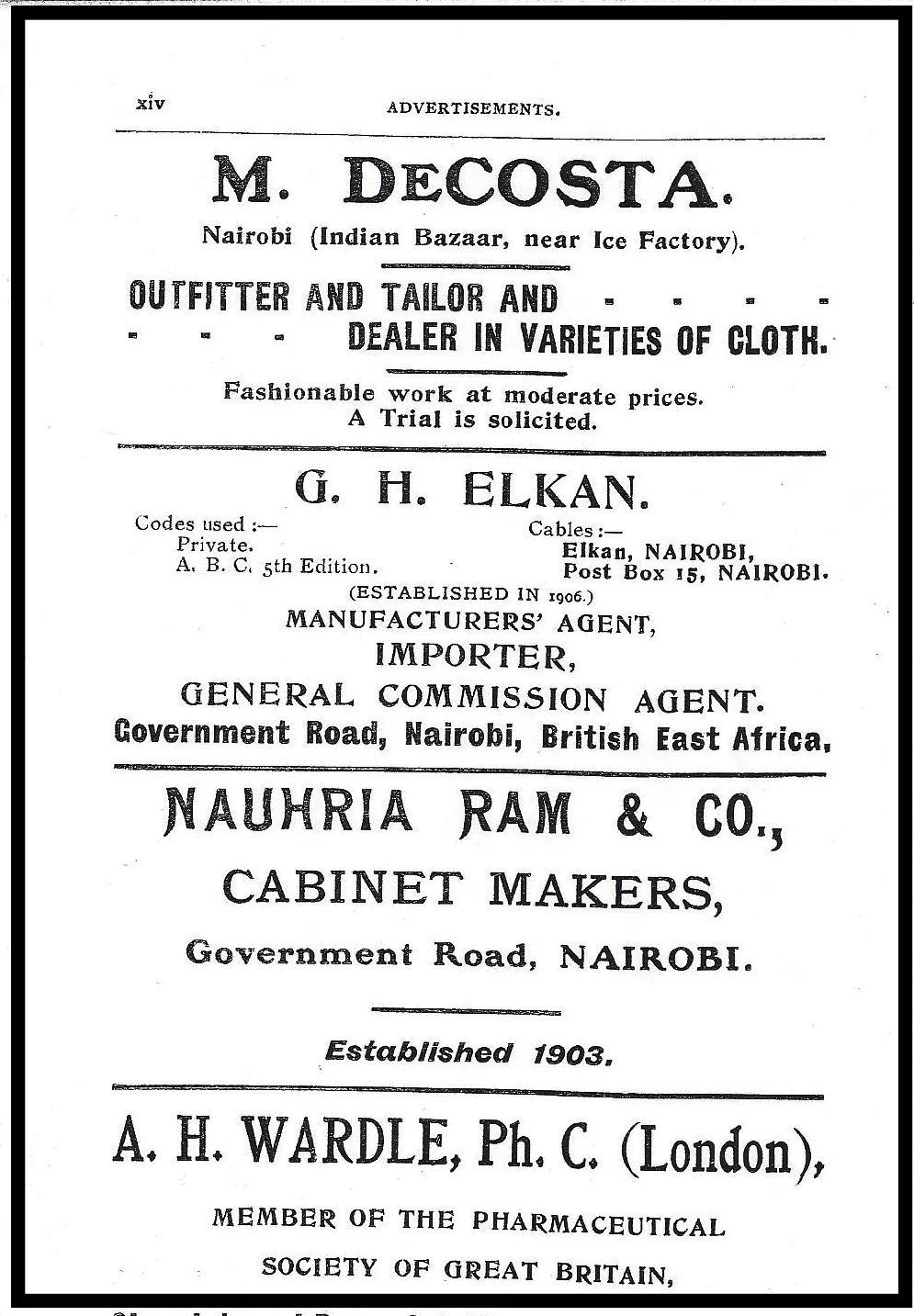

A Goan tailoring outlet located at the Nairobi Indian bazaar advertising in the Kenya Directory of 1920. Courtesy Clifford J. Pereira.

Lynch does get the next piece of the story right. Sabby, upon arriving in Mombasa, travels to Nairobi and resides for a long period of time at Mrs Sequeira’s lodging. Boarding & lodging facilities and hostelries provided by Goan families, were fairly common across colonial East Africa. A predominantly male migration necessitated such arrangements which made available room and a home-cooked meal at an affordable price. It is a working class population, particularly tailors, who were likely to have been their main occupants. Elite Goans lived in government-provided quarters or acquired land to build fairly substantial houses.

Sabby starts working for Ali Bux. Ltd, a men’s textile shop. This too complies with historical accuracy. Tailors arrived in East Africa on the back of the large retailer many of whom, like the Nazareth Bros and Souza Junior & Dias, were Goans. Their retail shops had haberdasheries attached to them providing fabrics, curtains and upholstery. As a natural extension, the retailers provided tailoring, and shoe & boot making services. It is likely, the tailors sat in the verandah of these shops and operated on a piece-meal basis. In later years, Goan tailors worked for Indian tailoring shops operating in the bazaar areas. Steadily, tailors opened up their own establishments and grew to be prosperous businessmen with assistants of their own.

A curious aspect of the book is that Sabby, from 1916 until his death in 1970, (yes, the narrator narrates his own death) spends an enormous amount of time pondering on the indignities heaped upon indigenous Africans by the colonial administration, the three-tiered segmentation of society and the usurpation of land from indigenous populations. This goes entirely against the grain of historical realism in literature. Goans were a colonised people and there would have been nothing shocking about institutional racism in British Africa as much of it prevailed in Portuguese Goa.

Ironically, written records dating back to 1900 reveal just how racist Goans themselves were towards African populations. They thought them inherently lazy, delinquent and inferior to Asians. They refused to school with them or even sit next to them in church. Only by accurately depicting the chosen time period, can writers evoke a sense of injustice in their audiences.

What should have been the pivot of Sabby’s interior monologue is the painful exclusion of the tailoring community from the lives of elite Goans. But this is addressed only peripherally (pp 100-102). In actual fact, a collection of oral histories of former East African Goans deposited with the British Library (Kings Cross) reveals the extent of the discriminatory practices faced by this community. The founding constitution of the Nairobi Goan Institute put in place in 1905, had as its guiding principle that ‘no other than a member of the Goan community of good social repute shall be eligible to the membership of the institute.’

Throughout the townships of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika (now Tanzania), tailors continued to be excluded well into the 1950s, from the privileged social institutes Goans fostered. Only in Malawi where numbers were considerably low did some sort of solidarity exist which allowed tailors to be members of the Malawi Goan Social Club. The irony was, many of these tailors with thriving businesses of their own, were financially far better off than civil service clerks. Catering to a mixed client list of Europeans, Asians and Africans their shops were neutral spaces of racial cohesion. They gave back to the African economy by training indigenous Africans in the trade and they had close ties with the Catholic Church in East Africa often holding fundraising events - such as theatre performances - to boost church coffers. As Lynch narrates through Sabby, outside the stifling bounds of Goan society, their children encountered great leaps of social mobility, acquiring higher education and pursing professional jobs particularly in the field of teaching.

Unfortunately Lynch fails to draw adequately on family history to present a compelling portrayal of the subaltern but hopefully her book will encourage others to pen their own memoirs and stories adding to our understanding of this important narrative.

Maria Lynch was born and raised in post-WWII Nairobi. She studied in London, England, and after returning briefly to Kenya, emigrated to Canada in 1970. A teacher by profession, Maria is now retired and lives in Toronto with her husband. Beneath the African Sun is her first novel. It can be purchased here.