“It was the Catholic Goans who actually taught the Iranis how to bake, the result was the Bombay pao.”

GAUTAM BENEGAL IN CONVERSATION WITH Selma Carvalho

Gautam Benegal was born in Calcutta and from early childhood showed a marked aptitude for graphic art. Later, the city lights of Bombay beckoned, and what followed was a flourishing career as a film animator, illustrator and writer. His two books, 1/7 Bondel Road (Wisdom Tree; 2011) and The Green of Bengal (Random House; 2014) have been critically acclaimed. Here, Benegal discusses the mapping of Bombay's cultural legacy through art.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Illustrations featured are © Gautam Benegal.

Gautam Benegal, artist, illustrator, film-maker and writer.

SC: We as a society have to redefine space. For instance when we talk about the 'West' now, we have to stop imagining a monolithic, mono-cultural entity. The West today is a multi-racial, multi-cultural space of shared values and purpose. Similarly, we have to redefine city space. It is no longer a transitory work-place with 'home' being elsewhere. Cities are instantly recognisable by certain commonalities - their modernity, homogeneity, and an anonymity which we both enjoy and abhor. Mumbai is an adopted city for you. When did you first arrive in Mumbai, what are your early memories and what do you think of the city today?

GB: Way back in my teens, reading those Louis L'Amour Westerns, one thing appealed to me greatly - the description of those campfires where strangers gathered and drank coffee - each one not knowing the other's name, swapped stories, and moved on. None displayed curiosity about the other's past. It was the frequent reiteration in those books that all kinds of people rubbed shoulders in the West: horse thieves, scholars, bootleggers, scientists, musicians - and the wrong kind of questions could get you killed. A man's past was behind him and done with. When I came to Bombay in the late eighties, I was thrilled to be given this advice by my 'import-export' roommate on my first night, in a boarding house in Chembur: Don't stare at a man's eyes directly in a crowded local train - he could turn out to be anybody. This was my Wild West where anything could happen and my destiny was mine alone.

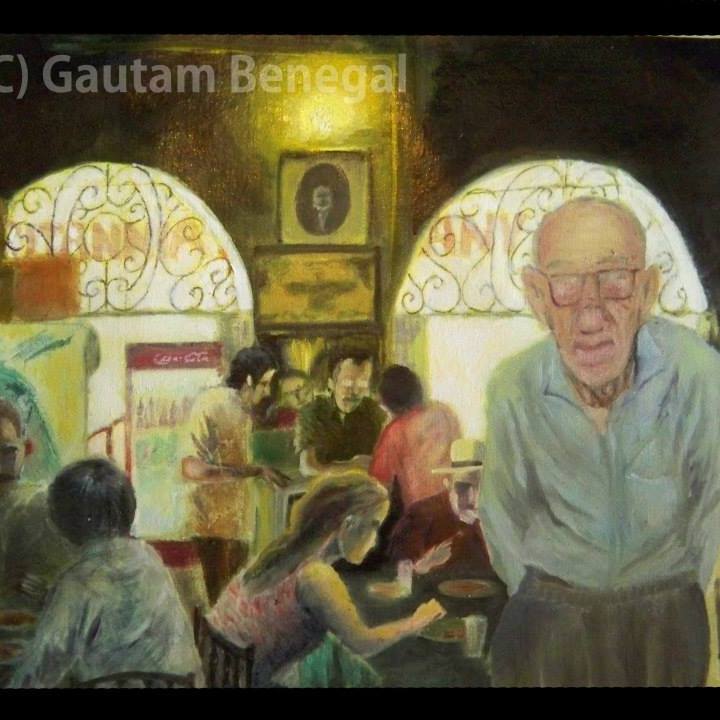

On Sundays, I'd walk the length of Fort and Churchgate, browsing the pavement bookshops, blow a major part of my week's earning downing beers in an Irani and take the Harbour Line home. For back then, Bombay was not just a place to make it - it was freedom. To live on one's own, with no societal obligations, free from the opinions of others and to explore dark and tantalising corners. This was a port city, an everyman's city, a frontier town and a bachelor's paradise.

In 1993, the meaninglessness, amorality and sordidness of lesser men leached the colour from the city, robbed it of its magic and left us with a husk called Mumbai. And if that wasn't enough, soon our trees would go, and a thousand malls and department stores would bloom in place of picturesque wadis and the hundred-year-old chawls. I watched as Dr Salim Ali's beautiful bungalow was pulled down and concrete took its place. The old houses of Bandra, Santa Cruz and Khar with their quaint, old names fell into neglect and legal disputes. Right opposite Crossroads Mall on Tardeo Road is a Parsi colony - understated, almost apologetic. It is easy to miss it on your way to Haji Ali signal. Old men and women peep out from behind faded curtains timorously at the huge blazing mall. It is hard to believe that these are the people who ruled Bombay once.

It was the rich tapestry of different communities that was so attractive, that gave this island its special place. My south Bombay friends used to joke, 'It is not part of India.' All India, yet definitely not part of India - for where in India would you find such inclusiveness and so much variety within a few square kilometres? But when the concept died, the city died. We let small minds decide the fate of Bombay. The entire city and its culture is being worked over with the twin brushes of uniformity and conformity. There will always be a Bombay. It simply may not be in Mumbai any more.

SC: How we view city cartographies has evolved. Cities are not determined by their brick and mortar. What is important is our engagement with the physicality of the city. The human mind recalls spaces by associating them with events. We remember, what being in a certain place at a certain time meant to us. And from that we determine a certain pyschogeography. You are trying to preserve this pyschogeography by mapping spaces through your art. How do you view the disintegration of the physical city (ii) how much of it can be preserved (iii) or are we left with consigning the past to museums, art and literature?

GB: We are the sum total of our memories. When memories fade the identity erodes, both individually and collectively. It is important to collate and curate community mnemonics in the form of verbal history and confluencing narratives as well as the landmarks that we connect with. There is a collective Alzheimer's of the soul that we are facing - especially in India - in our eagerness to embrace the baubles of the new and discard the worn out woollens of yesteryears from our cupboards. The emphasis on technocracy and disdain for the Humanities and Arts will prove costly in human terms in the coming years.

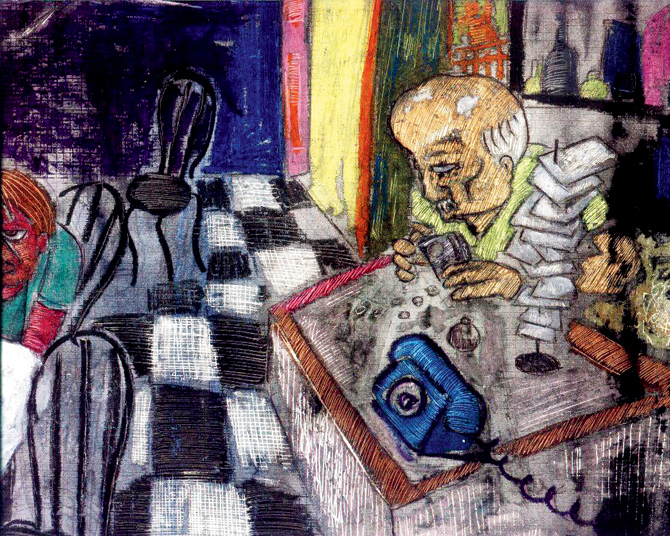

SC: Mumbai has a history of ethnic intersectionality. A recurring theme in your art is the Irani café. You are probably a latecomer to the Irani café, as I understand its heyday was the fifties. What is it you find so intriguing about the Irani café? Do you think Mumbai's intersectionality is fast disappearing?

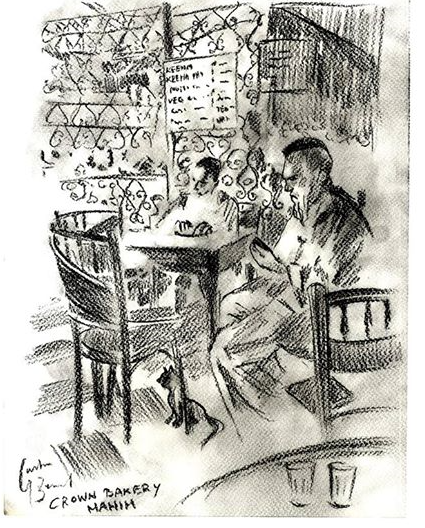

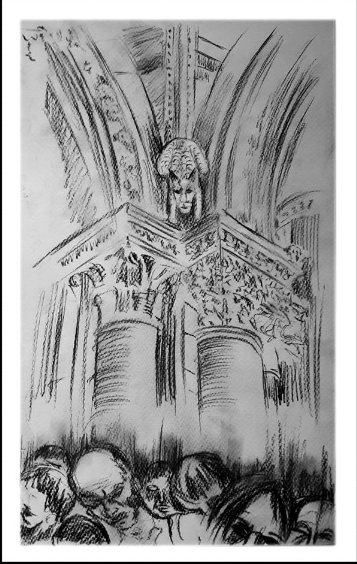

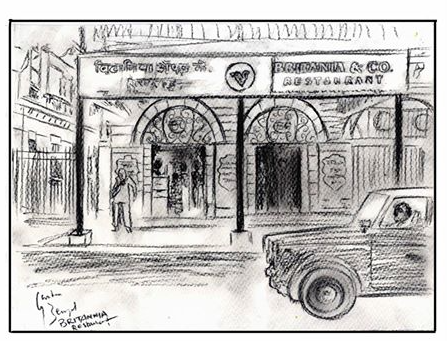

GB: I am an artist whose current interests are in presenting on canvas and mixed media the enduring space of Bombay. One of these motifs that run consistently through my work is the Irani café, and I have been exploring and researching the Irani café in Bombay for the last five years, presenting their various dimensions through paintings and articles, and now, hopefully the audio-visual medium. The Irani cafes are an unique feature of the Bombay cityscape, once found in profusion, but now disappearing, and with it taking away some of the earliest recorded instances of coexistence and secularism that it once symbolized.

SC: In the newly released children's book Boo: When My Sister Died by Richa Jha, a soulful story of a young girl coping with the loss of a sibling, one illustration in particular by you, depicts the Luso-influenced Catholic pockets of Bombay - what you might call old world Bombay - predominantly populated by the East Indian and Goan communities. What physicality of the city is best associated with these communities?

India is not the boiler pot culture that the invasive North is painting it out to be. Homogeneity was never our strong point, nor does it describe us. We are a tapestry culture. The goathans (Marathi: village) of Bombay are an integrant part of this tapestry. The cobbled narrow lanes, the INRI crosses, the red tiles on the bungalows, the bakery in the corner, the celebrations during Christmas that involves every member across communities, whether they are suppliers or consumers, these knit our society.

SC: In other charcoal drawings such as the Dias Bakery, you have been keen to capture the East Indian/Goan space. Is that because you feel they are under threat?

GB: They are very much under threat. It was the Catholic Goans who actually taught the Iranis how to bake, and the result was the Bombay pao. Very few know about this. There is a rich history of confectionary - the pastries, cakes, puddings and patties that they brought with them. Many of these recipes are disappearing.

SC: What are your hopes for the future of Mumbai city? How, for instance, can there be reconciliation between wanting to preserve its (often crumbling) legacy on the one hand and the urgent need to provide liveable urban habitats for its burgeoning population?

GB: Bombay is bursting at the seams. But that is not the real problem. The real problem is the homogenization, and the uniformity that is being injected into this once cosmopolitan city. Cloistered small minds collectively can be disastrous to a plural all embracing city like Bombay, and encouraged by the present government of India which is hell bent on forcing Hindi and North Indian culture down our throats and systematically 'othering' and wiping out the other communities is nothing short of cultural imperialism.