By Selma Carvalho

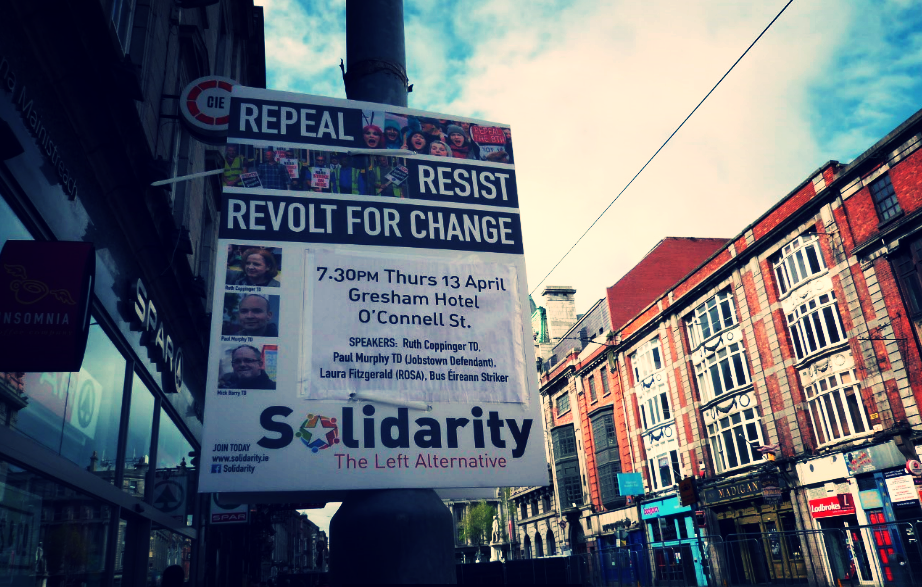

When I arrive at seven on a Saturday morning, like most good Catholic cities, Ireland is in deep slumber. I am in the land of rain and melancholy with streets sparsely peopled and shops shuttered down. The rain has arrived, as if on cue, to greet me. It’s not a grand deluge, worthy of deference. It’s a slow, icy-cold spitting which eventually, no doubt, forms character in people and cities alike. Dublin, from the Irish Dubh Linn meaning ‘black pool’, presents itself as London’s dowdy cousin but like most dowdy cousins, used to neglect, it’s developed grit and defiance - insurrection is everywhere, you can smell it in the potato.

This is no easy story to write. This city, Britain's oldest colonial conquest, has suffered. It is layered with the histories of successive invasions, one ruinous boundary wall atop another, recalling virtuous victories and mangled defeats. The Vikings, the Normans, the Danes, the English; the blood of Irish rebellion runs through these ancient streets. It has seen its young men hung, it has endured abject poverty even as the city spread from the muddy swathe of the River Liffy. Fuelled by arrogance, there rose the might of Anglo imperialism; the all too familiar Gothic spires, the fluted Georgian columns, the bare-faced Regency walls and stately Anglo-Irish settler houses on either side of the river-front.

On that same river-front is the Famine Memorial by Rowan Gillespie - six people cast in bronze, diminished by the vagaries of life embarking on a sea journey - which commemorates the potato famine migration of the mid-1800s. Its counterpart is in Toronto, Canada, showing just five arrivals. So dire was the loss of human life, swallowed by the sea, that arriving boats were dubbed ‘coffin ships’ having lost half their passengers in the crossing. Over a million people perished in the famine-related ‘Great Death’ but a million more successfully migrated to North America, making it the first wave of economic refugees to overwhelm American borders.

Even as the people sank under the weight of taxation and crop failure, the city’s building continued unabated amidst protests of it being excessive. The philanthropist Edward Wakefield railed, ‘A city, which contains in miniature every thing to be met with in the great capital of the British empire, is an object of attraction to the wealthy, the idle and the dissipated.’

The Irish feel unfamiliar. They are not English, those pasty men who conquered half the earth, the spillages of their conquests – the language, the religion, the culture – having seeped into the imagination and aspiration of distant people. But the Irish are not entirely insular either and not unknown to Goans. As intrepid missionaries, they filled the naves of Catholic churches and the corridors of Catholic run schools in the colonies. It was in East Africa, that the union between the Irish and Catholic Goan would reach its zenith. They worked together to build churches and schools. And it is the Irish, that Goans remember most fondly, when in the 1960s, they emigrated to England, and found themselves in an alien country not particularly welcoming of strangers.

As a Goan, I find there are other parallels to be drawn, notably at the Dublin Writers Museum which sits on the corner of Parnell Square in a beautifully restored 18th century building. Like Goa, the emerald isle, Ireland, produced writers disproportionate to its size. And like Goans, the Irish wrote in a language foreign to them, ‘the language of the invader fuelled the literature of the subversive.’ Their earliest forms of literary expression were poems of praise, satire and laments.

There before me is the face of Oscar Wilde. And it is hard now, not to be discomforted by the thought, that this man of almost ethereal beauty and grace, of wit and wisdom, of words and letters, spent two years in an English prison for his sexuality. So dismembered was he emotionally from that experience, that he died not too long after being released. While in France, he wrote his last poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol (which incidentally, I learn in Ireland, is pronounced as jail). Wandering aimlessly and in penury around Europe during the last three years of his life, upon his deathbed, he reportedly said, ‘My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has got to go.’

Also like so many Goan writers of the twentieth century, Irish writers wrote in self-imposed exile, mainly in London. But Ireland was ever present in their writing. In one of the glass displays is a poem by Donagh MacDonagh, ‘Ireland made me and no little town, with the country closing in on its street.’ As a sepulchral evening sky settles over Dublin, I slip into the city’s arterial roads, the smell of coffee and the soulful songs of street musicians, remind me every city pivots on a point, and in Dublin that point is resilience.