John Lawrence Nazareth was born during the post-war years in Nairobi, Kenya, the son of J. Maximian Nazareth and Monica Freitas Nazareth. His father was a prominent lawyer, nationalist, one-time president of the East Africa Indian National Congress, an elected member of the Kenya Legislative Council, and appointed Queen's Council in colonial Kenya. His grand-father J. A Nazareth together with his grand-uncle R. A Nazareth, operated as the Nazareth Bros. and were successful retailers, contributing much to the founding of Nairobi between 1899 and 1910. Here, Lawrence describes his early years when the family lived on Forest Road. This extract is taken from his memoir Up and About in Nairobi and Bombay. Please click on the link to read the full memoir. 101 pages. Contains family photographs.

By J. Lawrence Nazareth

Recollections from my childhood and early youth seem to have no definite timeline. Instead, they have coalesced into individual pools of memory and are ringed with golden auras that stand out against the dark, deep background of all that has been forgotten.

My earliest recollection is that of being seated on a hardwood floor and peering down into a darkened hole in a floor-board when I was little more than a year old. It is more a presence, or should I say a pre-sense, a memory of something that may not have happened. For me, however, it is real, my sole link to the “wood-and-iron” house of my birth --- “wood” because that was the material of its construction and “iron” because its roof was made from corrugated sheets of that metal. Shortly before my second birthday, my parents were fortunate enough to be able to move to a small stone bungalow about half a mile down the road, away from this wood-and-iron house in which they had lived in the first years of their marriage along with my father’s unmarried sister, the widow of my father’s eldest brother and her children and, at one time or another, two other brothers, one of them newly married. Houses were scarce in the years immediately following World War II. The wood-and-iron house has long since disappeared though I remember walking past a similar structure as a child with my younger sister and brother on our way to church.

Seen here Ralph A. Nazareth (Lawrence's grand-uncle) with his family. He and his brother J. A. Nazareth rose to prominence when in 1903 they landed the catering contract for the Uganda Railway.

The stone bungalow was rented from my father’s eldest sister, Natividade, who had built it for her elder son. She was a large, slow-moving woman, soft and infinitely weary, who lived in the house immediately adjacent, within the same compound. My younger sister and brother were born in that bungalow. Like its more impressive neighbor, it is now in a sad state of disrepair.

Of my brother’s birth I retain another of those pools of memory: being placed next door in the care of Aunty Nathu and assured that the baby was soon to be dropped from an airplane. The traditional stork would surely have been simpler and less dangerous but I clearly remember that it was an airplane. I recall looking upwards anxiously at the sky, fearful of missing the moment of landing.

I lived my childhood, up to the age of twelve, in that house on Forest Road, and the memory of those years is best captured for me by the opening stanza of Fern Hill , a poem by Dylan Thomas:

“When I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green”

Those for me were the apple days, my princedom my aunt’s large compound within which our bungalow was located behind a tall kai-apple hedge --- a plant of South African origin with little apricot-like fruit that ripen from hard green to soft golden yellow. It grew along the unpaved path for non-motorized traffic --- pedestrians, bicyclists, and the occasional rider on horseback---that bordered Forest Road and demarcated the front boundary of the compound.

This photo taken by district clerk Thomas J. Lobo is a good indication of the terrain of mid-twenthieth century Kenya.

As I’ve described in some detail in A Passage to Kenya, Forest Road took its name from a narrow fringe of forest, varying from one to three miles in width, which once grew on this land. A chronicler of early pioneering days, Errol Trzebinski, described this strip of forest as “impenetrable” and “magnificent”, a place where animals followed secret paths and visitors were entranced by the foliage, butterflies and flowers. But as Nairobi grew progressively, from a railway station and frontier town into the capital city of a newly-established colony, the forested fringe had given way to segregated, residential suburbs; for example, Parklands and Muthaiga, where only immigrants of European origin were permitted to live. The flora and fauna receded into smaller, isolated forest preserves or into the vast, mysterious, and dangerously lonely stretch of forested land known as the Nairobi City Park. This park lay immediately beyond the sports fields of the Indian community, in particular, the Patel Club and the Sikh Union, which bordered Forest Road to the north, while along the entire length of this road to the south, within gated compounds, were the homes of families of Indian origin---Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Parsees, Goans --- comprising another segregated, residential suburb of the city. Aunty Nathu’s was one of these compounds, and it had retained a little of the magic of that earlier pre-colonial time. Within its hedged boundaries grew a large variety of trees and shrubs, many of them fruit or vegetable-bearing, which had been planted by an unknown hand to replace the indigenous forest. It was a garden of delights, enormous in the eyes of a child. And, whilst the wild animals of the forest had long retreated into the confines of the Nairobi National Park, on the southern outskirts of the city, or to the open Athi plains beyond, the butterflies and birds of the forest had remained. Despite the passage of time, I can reconstruct with precision the layout of the grounds. Between the two houses grew the centerpiece of the compound, a huge mango tree with branches that spread over our red, corrugated-iron roof and bore plentiful fruit in season. As a child, I loved to clamber up into its lower limbs to pick a semi-ripe mango, which is delicious when sliced around the large seed and the flesh laced with a sprinkling of chili-powder and salt. This area between the two houses was a mini-orchard in itself, containing a pomegranate tree, alongside a spreading fig bush that yielded fruit which turned from green to dark purple. And beside it grew a little banana grove.

Next to our front bedroom window was a spreading mulberry bush and, behind the house, a tall mulberry tree. In season, it carpeted the ground beneath with furry, deep-purple berries. A sweet-potato patch spread wild, covering a wide area behind this mulberry tree. This was an especially joyful place for me, because within the foliage were to be found lady birds, insects smaller than a child’s finger nail, spotted and polished like brightlycolored beads, most commonly red or orange with little black spots. Most often they would fly off when I tried to capture them in my enclosed palm, but sometimes I was successful, once even succeeding in imprisoning a little collection in a matchbox. It is said that these pretty little creatures could crawl into your ears when you were asleep and, on that pretext, my six-year old sister, Jeanne, took it upon herself to release back into the garden this precious collection. In the ensuing uproar, Njoroge, our Kikuyu cook was dispatched to the sweet-potato patch to gather replacements, my protests silenced, and my sister suitably admonished despite the dangers she had supposedly protected us from.

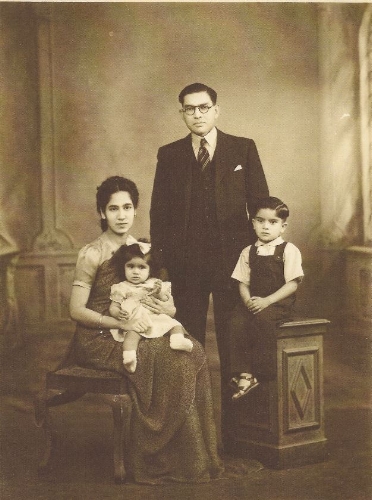

J. M Nazareth with wife Monica and children Lawrence and Jeanne. Kenya, c. 1950. Photo is courtesy of Lawrence Nazareth and cannot be reproduced without his permission.

A well-trodden footpath demarcated the boundary of the sweet-potato patch and it led from our back door to Njoroge’s living quarters at the rear of the compound. In addition to skills in cooking and capturing lady birds, Njoroge was very adept at removing jiggers, nasty little members of the flea family that lived in the black cotton soil of the compound. We children were cautioned never to go out in the compound in bare feet, because one ran the risk of a female jigger burrowing into the exposed skin and taking up residence to lay her eggs. Left unattended, this wound would fester and ultimately even turn gangrenous. So a jigger had to be removed promptly and carefully using a needle, whose pointed end was first sterilized with a burning match. Less threatening creatures called ant-lions also inhabited the black cotton soil and they fascinated me greatly. Their burrows were marked by little inverted cones of very finely sifted soil. If one took a twig and carefully worked it round and round within the fine grains of soil, one might unearth one of these little creatures before it could burrow deeper. I’d spend happy hours in search of them.

A little lemon tree grew within the sweet-potato patch and, on the other side of the path, about twenty of thirty yards from our back door, was a lemon-orange tree, the result of a cutting from a lemon tree being grafted onto the root stock of an orange tree, or perhaps it was the other way around, yielding a hybrid that bore both types of fruit on its two main stems. And next to this hybrid was another large mango tree, somewhat smaller than the one between the two houses and nowhere as productive.

The lemon-orange hybrid, however, retains a sad pool of memory for me. One morning, when the sleep had barely fallen from my eyes, I wandered down the L-shaped passageway that led from the bedroom shared with my two siblings, still dressed in my pajamas and with my catapult in hand. Looking out the back door, over the couple of small steps that led down to the back yard of the house, I spotted a movement in this far off lemon-orange tree and without aiming at anything in particular I fired off a shot in its direction. To my surprise, out dropped a little red robin, stone dead! These tiny birds, which have a deep red breast and a brownish back and wings, weigh less than an ounce and are much smaller than their American counterparts, which also happen to be called robins. (The latter are longer and leaner looking, generally have orange breasts and grayish wings and are at least twice the size and weight.)

By some unfortunate accident of fate, this little red robin had perched on a branch within this tree, directly in the line of fire. But, instead of delight at my unexpected success, my reaction, when I picked up the lifeless little creature from where it had fallen to the ground, was to be heart stricken. I was overcome with sadness, and, thereafter, I lost interest in my catapult. The reason why hunters and fishermen find pleasure in tormenting and killing living, breathing creatures remains a mystery to me to this day. I can recall another unexpected encounter, but this time rewarding, in the backyard of the compound. One morning, a huge tortoise appeared, seemingly out of nowhere. It must have crawled out of the Nairobi City Park and through the playing fields, crossed Forest Road at night when the traffic was minimal, and then into our compound. It stayed for a few days and then it was gone. A silent visitor from an alien world!

John Lawrence (Larry) Nazareth was educated at the University of Cambridge (Trinity College) and the University of California at Berkeley. He is a mathematical and algorithmic scientist, industry consultant, and university professor by vocation and an avocational travel and memoir writer, poet, essayist, and playwright. He makes his home on Bainbridge Island near Seattle, Washington, USA. His book A Passage to Kenya (2017) can be purchased here.