“In my search for the answer and in learning about my parent’s histories, an unexpected revelation about my identity occurs. My Goanness was lost in a hostile and unwelcoming environment.”

By Dina Lobo

“I remember I used to take almost a hundred bites just to eat a small piece of bread. You can’t even imagine how long I would take to chew to make that bite last.”

My father recalls a humbling moment three months into the Gulf War in Kuwait, in which food was scarce. He walks me through his sensorial recollections of 1991. Black skies for weeks as he was unable to distinguish morning from night due to the firing of oil wells. The background echoing with noises of rockets, explosions, and gunshots that made sleep difficult. He smelled smoke so thick it could choke a person. He tasted a dry mouth, water ever scarce. Most vividly, he remembers a soldier’s gun to his temple as his pockets were emptied of the last 90 dollars he had withdrawn from the bank before it shut down. This scarcity and fear was in sharp contrast to the abundance he had enjoyed as a bachelor in Kuwait before the war – a life of financial and personal security that took ten years to build since leaving Goa at the age of 21 after my grandfather suddenly died of a heart attack.

Our Goan family’s relationship with Kuwait started with my grandfather working in the Gulf as a petrochemical engineer. At the time, my father, who was five, attended boarding school in Marcela, Goa. Upon my grandfather’s death, my father who was the eldest of eight siblings, was faced with the sudden responsibility of providing for them. Having recently graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Business, Kuwait felt like a fruitful option. He began to flourish once he found employment at a company in 1982 (one he stayed at until he left Kuwait in 2011). It was also the place he met my mom.

Marcela

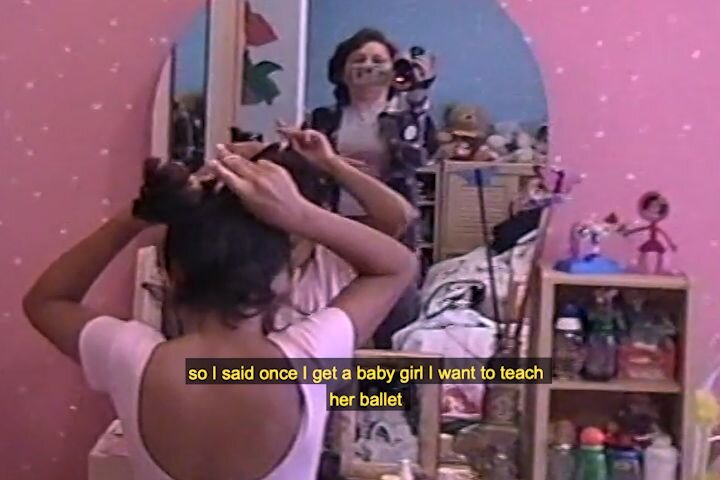

In 2020, I made a short documentary titled Marcela. Named for my dad’s hometown in Goa, it is where my grandmother’s house exists to this day. This house is shown several times throughout the film when mentioning a vacation we took to Goa as kids. The name of the town of Marcella is derived from the Latin word meaning young warrior. Because I had neglected my Goan identity for years, the title felt fitting for how the film ends as I begin to embrace that identity. The film uses my family’s personal archival VHS footage that my mom filmed as I was growing up. Additionally, I interviewed each of my family members – my father, mother, and younger brother – to explore the film’s central question: After many years of practice, why did I quit ballet as a young girl living in Kuwait?

In my search for the answer and in learning about my parent’s histories, an unexpected revelation about my identity occurs. My Goanness was lost in a hostile and unwelcoming environment. Losing my interest in dance, in the film, parallels the loss of a part of my identity. At the same time, I contend with my father’s internalized racism, itself a product of the discrimination he experienced. I made this film as part of my Master’s thesis in documentary film, never considering the context of the Gulf War and what that meant for my father. Much of the making of the film helped me to discover how my own identity was rooted in the post-war decisions my father had to make.

Where it Began

My parents were work colleagues for years. With most of my father’s family living in Goa, my mother’s family – especially during the war – became his sense of “home” because most of her kin were living in Kuwait. With familial connections growing, my father claimed that he came out of the war with a new perspective and decided to marry my mom, the start of many changes. Despite his initial feelings of patriotism towards Kuwait, after the invasion my father’s sentiments began to shift immensely, especially due to the country’s instability and glaring xenophobia. He began to realize that despite how hard he worked, something about him was never enough. The effect this had on him changed the narrative of home, not only for himself, but for his kids, for me. The goal became to leave.

I was born in Texas in 1994 during a business trip my father made to the United States with my mother. Upon returning to Kuwait, as someone who was the product of the union of a Syrian mother and a Goan father, I had trouble forming a defined sense of self and also because of my childhood spent in an American school in Kuwait. Despite being born in America, Kuwait is the birthplace of my origins and where my parents met. It was also the country where I attended ballet lessons at the Kuwait School of Dance between the ages of four and twelve.

Even as a child, through my experiences in school, at ballet, and among friends, I understood that Kuwaiti citizens held immense power and privilege. Since the oil boom in the 1970s, Kuwait, like other Gulf Cooperation Council countries, relied on an influx of foreign workers from South Asia to work lower-class, labour-intensive, and unskilled jobs. This othered South Asian workers and fuelled xenophobia in the region, even colouring how white-collar South Asians like my father were perceived.

Quitting Ballet

As I revisit the reasons I quit ballet in my film, I draw on an event that was the catalyst to that decision; a vital auditioning process in which I had the potential of landing my first lead part. In the narration, I recall learning unofficially from the co-owner of the dance school that I had gotten the lead following the auditions. Except, on the day of the results, I found out otherwise. Leila, a Kuwaiti ballet student I grew up with, and whose mother was friends with the main owner of the school, had gotten the part instead. Although there is no evidence to back this claim, in my film I imply that wasta, a common practice of relying on influential connections in Kuwait, played a role in the casting process.

The viewer is left to assume that these were the events that led me to quitting ballet. I may not have understood as a child that I had experienced racism and witnessed nepotism, but it is apparent in the film’s retelling of that moment. Quitting ballet was never about dance and was always about the inkling I had that somehow no matter how well I performed or worked, something about me was never going to be enough.

Identity in Progress

Hearing from each family member throughout the film, I come to the conclusion that I was deliberately kept from connecting deeply with my Goan roots. My father never taught me Konkani, his language, and my only connection with his homeland was one summer vacation there as a child. The question I began with about why I quit ballet opened the door to many more questions about why I had not been taught about Goa.

There is a moment in the film that is the most emotionally significant to me. It’s when my father tells me the reason why he wasn’t often present at my school plays or to pick me up after classes let out. This was to keep anyone from realizing that he was my father, to keep the fact of his ethnicity from projecting on to me. From this vulnerable revelation, I learn of all my father had internalized in Kuwait. It then became all too clear why he had downplayed his identity and did little to pass it on to my brother and me. In the film, my brother reveals how he “never feels Indian.” This lack of a sense of belonging is perhaps a product of my father’s deliberate attempt to not acculturate us as South Asians.

By engaging with my father’s experiences in Kuwait, Marcela does not simply chronicle immigrant life or my family’s past during the war; rather, by making this film and continuing to have conversations with my father about the past, I am reminded of the importance of delving deeper into family history.

Dina Lobo is a filmmaker, artist, and writer based in Toronto, Canada. After directing her first documentary film in 2016, she found a love for visual storytelling. By making the personal political, she is interested in exploring the more intimate, fragile, and vulnerable truths of the subjects and themes that contextualize her films and creative writing. Recently graduating with a Master’s of Fine Arts in Documentary Media from Ryerson University, she is already working on her third film.