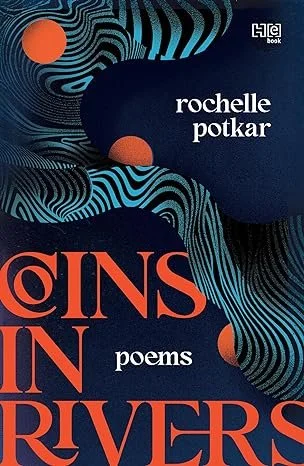

Reproduced by kind permission of Rochelle Potkar and Heta Pandit

Two powerhouse writers sat down at Dogears’ Bookstore in Margao on 7 June, 2024, to talk about poetry. Heta Pandit, the consumate conservationist, who has put all her energy into researching Goan architectural styles, a founder-member of the Goa Heritage Action, and the author of 11 books on Goan heritage, and Rochelle Potkar writer and poet of numerous works including the much acclaimed short story collection Bombay Hangovers, and the poetry collection Paper Asylum, shortlisted for the Rabindranath Tagore Prize. Under discussion in the cosy corners of Dogears was Potkar’s latest poetry collection, Coins in Rivers (Hachette, 2024).

Heta Pandit: Why do we call it a book release, Rochelle? In fact, isn’t it just the reverse of release? Holding, reading, and experiencing a book is an inhalation, a holding in of your breath, a waiting for a revelation. That is exactly how I felt when I began reading Coins in Rivers. I wonder why the perpetrators of all the atrocities described against women are men. You write as a feminist; you see and understand scars. Even the ones under the skin. And yet, I see a soft gentle touch, not the caustic, harsh, and scarred perspective of a hard-core man-hater. If I were to collect all the coins you have tossed into rivers, I would indeed have enough to fight an election.

What follows are Pandit’s introspective takes on a number of Potkar’s poems.

“Keyholes”

“We hide our wet lace behind a trellis of plants,

Our voices honeyed from jaded soap operas.”

Keyholes is not just about bloodshot saffron eyes, it is also about the male gaze, the fear that a landlady has, based on her own personal experiences, a fear she translates into distilled and selective restrictions, a fear of girls turning into women, a fear that they will have bodies that will disobey and hormones that will go astray, a fear of transmutation after sundown.

“In that land under the sun”

“In that land under the sun, where dry heat hits bone”

In that land under the sun, while the woman keeps away (why does she not keep aside?) a mountain of grated coconut over flattened rice, sugar, coffee, and unused milk, par-boiled… she also tucks her wet sighs at the edge of her sari. With her wet sighs, Rochelle, she also tucks away her wet dreams, her moist damaged vagina, her cramped style, her inner self, her naari shakti, her personality. Suppressing her might be the only way to control her will or her witching.

“Three women on Liberty Bridge”

“As the light dims, travel stills,

The bridge aligns itself to darkness”

Three Women on Liberty Bridge may not appear, at first read, romantic poetry but to me, it is a romantic, feminine, feminist story. It is the wordless story of speechless, sparring (but tentatively) only within the small, tight circle of the three women. Women, whose eggs, like their thoughts and their speeches, are waiting, under the frozen “eggs of civilization.” Until it is spring, again.

“Prey”

“She waited outside an eagle’s nest

before its chicklet flew”

This is the story of a 13-year-old Mongolian hunter who trains her golden eagle to hunt and kill its first fox. We do not know if the eaglet is male or female. We do not know if traditional bindings will allow a 13-year-old to continue hunting. But we do know that if our hunter loses sight of her prey, she will be the one that gets eaten in that one split second.

“10 Things I want to do to you”

“Take your ears into my palms

Whisper prayers—"

I will start with 7. Dislocate your knees so when you venerate, fall to the ground, you are at once martyr, at once militant patriot, at once nationalist/character and caricature.” The poem is about fracture, dislocation, dissemination, deprivation, despair, deprivation, desperation, and a determined desire to consume, swallow, annihilate.

“Atonement”

“The restorer has walked in—brittle himself”

When things get back to normal after the rioting, the stampede, the unleashing of terror… but do they? The expert restorer does not quite exist. With all his “stereo-binocular microscopes strapped to his head, a fiber-optic light and all the gadgets in place” does the scent of fear, the memory of hate ever go away?

“War Specials”

“Spy pigeons, un-believing of borders”

Only Rochelle could have thought of paying a moving tribute, a prayer in a poem to all the animals that man has enslaved, tortured, and abused in wars. “And words?” asks Rochelle. “They have a separate gallantry.”

“Capsule”

“My heart is a bomb. And we wait for it to explode.”

It happens to all of us. We hear of trouble in the city that we once lived in. We call Mom and ask her if she is alright. “I’m okay,” she says. “It is in another part of town. Don’t worry.” Later, when people talk about it, we say we don’t know anything about it. “I wasn’t there.”

“Mask”

“He wore one when he was born”

is the opening line of this poem and when you get into the body, breast, and genitals of the poem, you also get into the “let wisdom seek through war paint. The breath you left is in our prayers. Bodies are weapons of healing/too.” Is that why we worship your face, your body, your beard, and the pockets in your breasts? And is that why the Buddha and the Prophet (Peace be upon Him) said that they did not want you to draw or sculpt their likeness? For then you will forget, they must have said. “The story remains the same.”

“The Earth Remembers”

“Her orange-spoted filefish and quivering

trees”

Just as the body remembers, the earth remembers. She remembers her old wounds, surgeries that were not necessary, injuries that were inflicted out of spite, hate, anger, or, simply because she was there, an innocent bystander, caught in the crosshair of unlovedness, neglect, abandonment only because she did not want to be one of them.

Ah, there is the light bulb again! “The earth remembers the heart of a drying lake, gut where all breathe an equal air of light-bulb-promises.”

“Displaced”

“The fish fly in the night to become stars”

I was a small part of the Narmada Bachao Andolan and have seen hundreds of thousands of tribals flow out of the forests in protest, infants suckling at their mother’s breasts as they walked with glazed eyes, their hair unoiled. I have heard their suffocated cries, stifled voices cry. Rochelle says that “some went into the mouths of the forest/some lay as still as mud/some left for the city shanties/ and some like Kalu sat outside their homes rowing a boat gently over the new river/stopping right at its center. There was no fish there, /where many, many feet below/his village, home, and fields still lay.”

“New World Order”

“These forms that carry knowledge

in algebriac shapes

of mythological immortality”

There was a time when we had gurus and gruhinis in every home. The heads of our households were both law-givers and law-keepers and the keeper of the keys (and societal values). This poem reminded me of how paddy grass mudas would be woven around the rice stock in the household and how these mudas were stored in the vasri, the wrap-around verandas in the courtyards. The mudas were under the watchful eyes of the elders of the house, mainly the karta or the head of the house. If a family member (in most cases the daughter-in-law) needed to draw from this stock, she had to seek his formal approval before delving into the muda to draw just enough rice for the day. A “good” daughter-in-law was the one who was thrifty and knew exactly how much rice to ration out for the day. These practices were defined, unwritten, and meant to last forever.

In the New World Order, however, “No forever is marked for them/by their elders/as constellations in night skies.”

Coins in Rivers is available for purchase in bookstores across India and on Amazon In or Amazon International.

Banner image by Wai Siew downloaded from Unsplash.com