Review by Glenis M. Mendonça

When a modest, retired high school teacher and former headmistress puts her heart into translating folk tales from the English oeuvre into Konkani, there is something amazing happening here. Irene Cardozo took over two years to read, select and gradually translate into Roman Konkani the legendary tales we have all read in English, and thread them into a book titled, Kirnnam (the rays). The book was published under the Bhurgeanche Sahitya Yeuzonn imprint by the Dalgado Konkani Academy in 2019.

Seventy-four stories are collated in this book of 201 pages. The title itself initiates the idea that each story brings a ray of hope for a better future. The children reading, are presented with a moral message by Cardozo at the end of each tale. Metaphorically, Kirnaam brings ‘rays of positive morality’ to a new generation, exposed as they are to questionable values.

Cardozo has painstakingly selected the best stories from varied sources and has faithfully translated them to the target language, Konkani. Tales from the Panchatrantra, Jataka, Aesop’s Fables, Akbar and Birbal, Christmas stories, as well as children’s classics in English, are knit together to form a cohesive work of literature. Always mindful of her target audience – children – she even provides alternate English words in parenthesis.

Eschewing the word-to-word, Formal Equivalence manner of translating, Cardozo chooses instead to adopt a sense-to-sense or Dynamic Equivalence (Nida, 1964) approach. The translator employs the closest equivalent word in the source language to ensure that the story blends well in the target language. Even titles are given a new twist to suit the Konkani ethos. For instance, the popular story ‘The Boy who Cried Wolf’, is re-named Fokandda Buzlim. Likewise, the well-known story ‘Androcles and the Lion’ is translated as Upkari Xinv meaning the grateful lion. The celebrated tale of ‘The Woodcutter and his Axe’, is translated as Sot Tench Uloi, speak the truth. In each of these instances, the English story titles focuses on the centrality of characters while the Konkani translation underlies the value-based morals the stories promulgate.

Several stories are skillfully translated with great effort on the part of the translator. Suropai ani Zonavor is a translation of ‘Beauty and the Beast’, narrated with fidelity to the source text. The curse is lifted after Beauty chooses the Beast over her family, and the Beast transforms into a handsome prince, as in the original text. ‘The Cap-Seller and the Monkeys’, is a favourite bedtime story rendered beautifully as Topiwalo ani Makodd, highlighting the presence of mind of the cap-seller in retrieving his caps from the playful monkeys. Among the select tales from Panchatantra, the translation of ‘The Foolish Lion and the Clever Rabbit’ as Xanno Sonso ani Xinv, is worthy of mention. The ingenuity of the puny rabbit outshines the dimwit king of the jungle as in the original tale. The narration uses simple language, comprehensible to young children, perhaps even toddlers.

Select Aesop’s fables are re-discovered in Konkani: Xinv ani Undir and Pixem Gaddum are translations of ‘The Lion and the Mouse’ and ‘The Ass Carrying the Image’. In fact, there are at least four stories besides Pixem Gaddum, featuring the donkey as a central character, making it a beloved animal in children’s literature (Gaddum ani Tachi Saulli, Gaddum zo ek Razkunvor Aslo, Gaddum ani tacho Dhoni and Gavpi Gaddum). Most of these stories are extracted from Panchatantra and Aesop’s fables. In almost all of them, the translator has made sure that the stories retain their original content and plot. The fluidity of the narrative using dynamic equivalence, and the felicity with which the translation is done, is well balanced.

J. B. Casangrande asserts: ‘In effect, one does not translate languages, one translates culture…’ Translation becomes a cross-cultural enterprise and the translator uses strategies to translate source culture into target culture. What is remarkable about Cardozo’s translation is her ability to indigenise or domesticate stories; to make them relevant to Konkani readers. The target culture of the Konkani community is treated with tact and sensitivity, and several tales are made to adapt to the Konkani ethos. For instance, the popular story of Little Red Riding Hood becomes Tambbdem Bai and the moral derived is: children should not speak to strangers. Likewise, the popular ‘Tattercoats’ by Joseph Jacobs, which narrates the tale of a young orphan who is ill-treated by her grand-father but who eventually wins the heart of a young prince, becomes Pinzkem Mari. Cardozo is acutely aware that the girl Tattercoats needs to become a recognisable figure in the Konkani cultural context, and hence she sagaciously chooses the name Pinzkem Mari (Maria/Mari being a common name among Goan Catholic girls). Similarly, stories such as ‘Cinderella’ (name retained in translation), the ‘Three Little Pigs’ (Tin Dukor) and ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ (Nhidloli Sundori) are familiar English classics translated skilfully. The illustrious tale of ‘The Little Mermaid’ by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen is brought to life in Konkani as Sirenetta, after the mermaid. Bebo Razkuvor is a creative rendering of ‘The Frog Prince’, while Razache Nove Kopdde is a felicitous translation of ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’.

There are several stories in Kirnnam which have a distinct Indian origin. Sopnam tim Sopnanch Urlim is a translation of ‘The Milkmaid’s Dream’. Cardozo has changed the milkmaid’s name from Radha (as in the source text) to Shanta, perhaps because the name rings familiar with girls’ names in Goa. There is the Arabian story ‘Ali Baba and the Forth Thieves’, the tale of Ali Baba who finds a treasure trove secreted away by bandits, translated as Ali Baba ani Cheallis Chor. So also, the Akbar-Birbal tales make their note-worthy presence felt in this collection. Birbal Fottounk Nam, Burgeak Samballop Kotthin, Akbar-an Dilolem Utor Pal’lem and Samratt Akbar-acho Rag Nivolltoto are creative translations from the opus, Akbar-Birbal. They embody the wit and wisdom of Birbal, the intelligent minister of Akbar’s court, and familiarise the Konkani readers with these personages from India’s history.

The book has an opening address by the president of Dalgado Konknai Akademi, Tomzinho Cardozo which outlines the need for children’s literature to be translated into Roman Konkani, as there is a scarcity of the same. A book like Kirnnam, he writes, can be read not just by children, but also enjoyed by adults to savour the nostalgia of bedtime stories. There is also a foreword by Willy Goes titled Bhurgiank Xikxonn Divpi Kannio, lauding the translator for being faithful to the original stories and retaining their authenticity to a great extent.

In her translator’s note (erroneously called Borovpiacho Sondex instead of Onkarpiacho Sondex), Cardozo notes the driving reason for bringing such a diverse collection together, is not merely to entertain, but instil good values. However, though the translation is well-rendered, the spoon-feeding of ‘morals’ is not necessary when appealing to an intelligent 21st century generation, who can interpret multiple morals within each story. Specifically stating the moral, limits the vision of the story receiver. Perhaps, there are other perspectives, ideas, morals and ideals which may emerge from an intelligent child’s mind… building up spontaneously as they read along. Why should pre-digested morals, stunt new ideas?

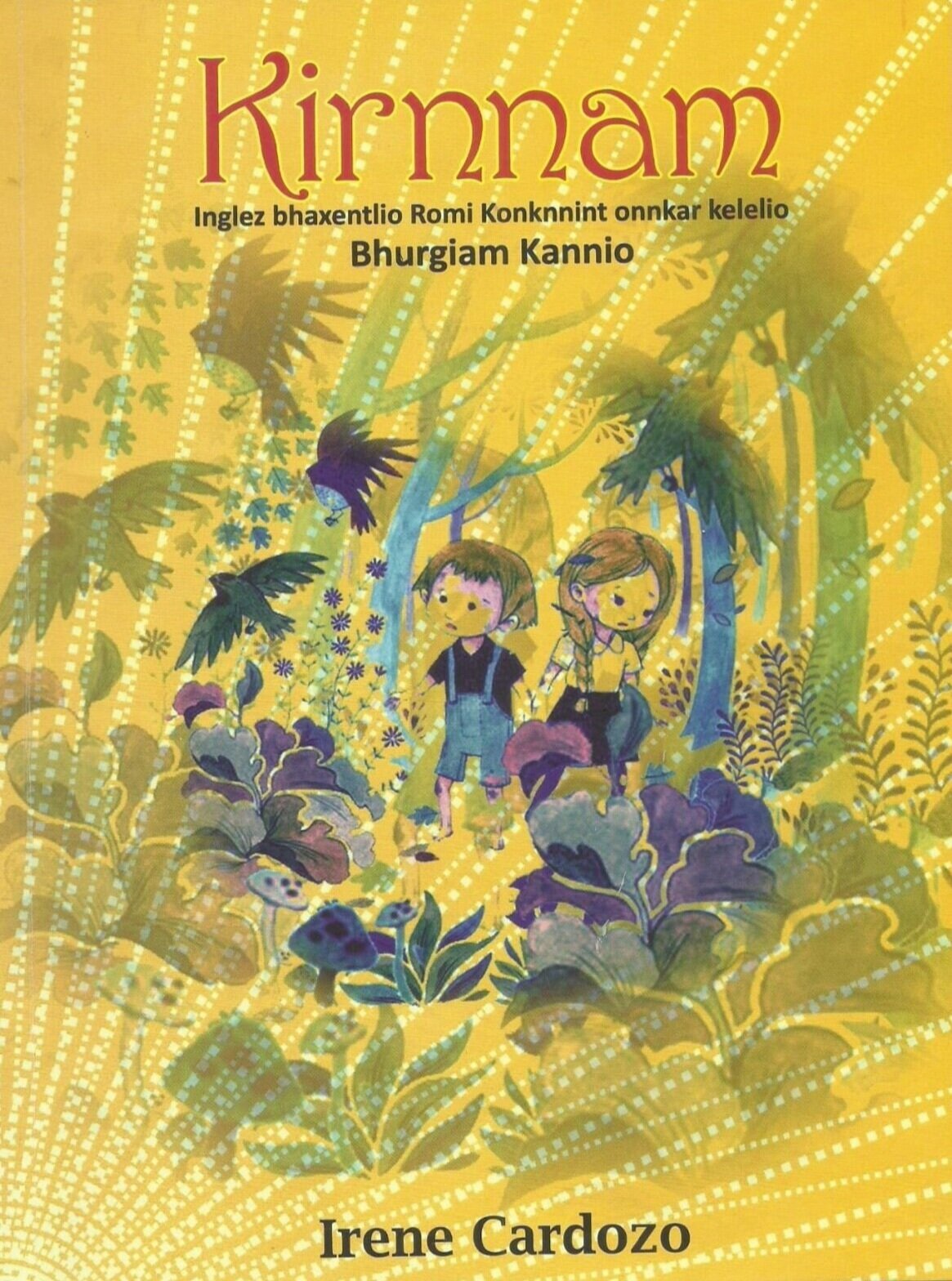

The bright rays of the sun shining on a little girl and boy surrounded by trees, birds and animals, is a befitting cover design credited to Willy Goes. Kirnaam becomes delightful rays of hope for Konkani lovers of children’s tales, and shines brighter as we re-imagine them from the Konkani reader’s lens. Cardozo’s work is commendable and needs to be appreciated not just by parents and children, but by researchers and scholars of Konkani children’s literature. If transcripted, this oeuvre can open new vistas for the dissemination of Konkani children’s literature across the Konkani-speaking world. Such a book can assist those working on Konkani YouTube videos or digital songs or adaptations/transcreations of stories, leading to an enrichment of the Konkani language, literature and culture.

Glenis M. Mendonça is Assistant Professor at the English Department of Carmel College Goa. Her Phd. thesis is titled, ‘Konkani Fiction in English Translation: A Critical Study.’

Kirnnam is available for purchase from the Dalgado Konkani Academy offices in Panjim, Goa. Or order on Amazon here.