By Savia Viegas

My efforts to trace the legendary Angelo da Fonseca’s Goa ties were impeded by too many cul-de-sacs; mental and geographical erasures had thrust the artist into an abyss of oblivion.

On my last mission to his natal island village of Santo Estevam, to locate the Fonseca home, I knocked on the door of a significantly old house.

‘Could you help me locate the house of Angelo da Fonseca?’ I said in Konkani to the woman who unbolted the door. The artist was a household name in his native village, I reckoned. The woman shifted her gaze from me, fixed it on the floor as if thinking, then asked me nonchalantly in English: ‘Which Angelo you want Baie, the bakerman or the tailor?’

This time I have help on hand. Delfina - Yessonda—the 53-year-old daughter of the iconic artist and I have decided to journey to the neighbourhood in Santo Estevam that once was the estate on which the ancestral Fonseca home stood.

The artist had moved away to Belgaum, Poona, Bombay, Calcutta and Poona again, to spend his adult life. He had played a vital role in India’s movement towards inculturation receiving the papal knighthood in 1955. Several other awards and honours had brought recognition to his work. At the time of his death in 1967 due to cerebral meningitis, he left behind an extensive archive of 1,000 works in gouache, watercolours, oils and soft pastels, now housed in Goa and different parts of the world.

At the Cumbarjua Ferry point, the old colonial-time ferry chugs back and forth chopping through the waters. I haven’t seen Yessonda for a good four decades; the last time I met her was when she was around ten, a moon-faced plump child, with a translucent complexion, exceptionally tall for her age.

During vacations, the mansion of Alice-mann, the niece of Angelo da Fonseca in Carmona would be abuzz with visiting relatives. In December, the table would groan with Christmas goodies of unimaginable variety, all personally prepared by Alice and her daughter-in-law. In the summer, the house would hold the aroma of varieties of mangoes with the dining table always displaying a still-life of cut fruits blazing colour in the heat-haze.

I loved Alice-mann and her fabulous stories of royal opulence, cavalcades and regal grandeur. Her youth spent in Junagadh where her father was a senior official in the royal revenue department had allowed her access to courtly life. Angelo da Fonseca captures the visage of the statuesque Alice as Madonna in a number of paintings. She was his sister Helena’s daughter, but also his peer as he was the youngest of 17 children.

In the May of 1967, I sauntered past the buffalo paths into the house of Alice-mann. Two girls about my age were standing at the French-windows of the sala, chatting. The tall girl was wearing shorts and a white short-sleeved top. Next to them sat a man in a block-print shirt. A petite lady in a cotton sari and a sleeved blouse was talking in a loud authoritative voice. Her complexion was tanned, and her nose was aquiline and strong. This was the Fonseca family on their annual visit.

‘Delfina has brought along a friend,’ Alice-mann said, pressing a slice of toast and pearada into my palm.

I don’t remember the ensuing events, but I remember bringing the short-haired ‘friend’ in a pale lemon dress to my house to play. But when we went back all hell broke loose and the petite woman’s voice pitch rose above the candelabra of the house. Of course, it was my fault—I had walked away with their little guest without informing anyone. That was my first introduction to Angelo, Ivy and Yessonda—the Fonseca family. Later, much later, when perusing the collection of the artist, I discovered a painting he had done on that visit to his sister’s house in Utorda. It captured Yessonda against one of the windows overlooking the square of their roz’angon.

As I recollected those times, a car dropped a woman with shoulder-length auburn-tinted hair. ‘Yessonda,’ I opened my arms for a hug.

The ferry puffed its way across the narrow strait. Yessonda’s eyes lighted up as we headed towards Marcel-Tonca across the river. The Fonseca’s sprawling estates here were visited whenever the artist came to Santo Estevam.

We did a little detour to one of the Fonseca estates.

A new temple has been built at Marcel-Tonca and the statue of the deity Ravalnath is being installed. The function was truly a sensorial feast. An ocean of bright silks of blues, saffron, red, greens and yellows opened before us. Women were taking prasad. A wafting smell of rice and accompanying curries burst in the air. Drums rolled and there was the whisper of a shehnai.

A sewak motioned the path to the estate. The terrain was rough and full of prickly dry twigs. Yessonda pointed to an oddly-shaped laterite-bound structure which resembled a well. ‘We bathed at this spring in childhood! Its waters were believed to have curative properties.’ Now the wellness spring is a shabby mess of rotting wood, stagnant water, and plastic bottles. Further into the property, Yessonda motioned to a ruin of stone and crumbling wood with a door lintel and a rafter or two. The structure was a nala lojja, a veritable store-house for the wealth of coconuts harvested every trimester. This harvest almost became a burden when the prices of coconuts fell, and the fortunes built on the coconut plantations became nostalgic episodes referenced in past tense. Fallen dry palm leaves from malnourished trees with swollen roots gave the landscape a desolate look. There is a huge anthill in the vicinity, and I am scared a king cobra may just pop up like in the stories from my childhood

Yessonda, caught in a tumult of memories recalls the taste of the times gone by: the tender coconuts, the cangi served with pickled thor, the kokum seasonings that Porob, the caretaker, supplied to the family with the thepla, the berry for the curry seasoning. The heat was oppressive and we heard the winding-up notes of music from the Ravalnath installation.

Back in the car, Yessonda reminisced about her father Angelo da Fonseca. A Gandhi cap, block-printed shirts and kolhapuris were his signature clothing. The bicycle was his only mode of transport. She followed him in all that he did during the day: shopped for vegetables, fish, cooked, dug around their little garden and painted. Fonseca was very much a man about the house; he liked to tidy-up, iron his clothes, cook – and dance he was a natural dancer. ‘My mother had two left feet, but my father loved to dance. Maria Conceicao, the adopted daughter of his sister Olinda, was his favourite dancing partner,’ recollects Yessonda. He was good at gardening, loved the theatre and played the violin.

Fonseca met the young Ivy, his future wife when he was 48 years old. The year was 1950 and Fonseca had returned a while ago from an extended tour of Europe where he had displayed his works across the continent. ‘My maternal grandmother moved to Sangolda, Goa, after her husband died in Lahore. The girls were young so were sent to Belgaum as boarders to study in English. This would be around 1940. She then moved to Kirkee (a town in Poona) with both the girls for higher education and her own job prospects. Her brother worked in the ammunition factory and was well settled.’

Ivy took up a teaching job in Poona. The artist and the young teacher met at a Kirkee parish. ‘Daddy was commissioned to do some paintings for the St Ignatius Church, Kirkee. Ivy the inquisitive, used to go to watch him and that is how they met. She was always in a dress as that was how the Christian young girls were attired. The influence of the sari came in with my father. She married in a sari and wore a mangalsutra.’

She came and sat constantly by the scaffolding at the Kirkee church where he was creating a mural. Smitten by the young, demure beauty who bore a resemblance to the vision of Madonna he sought to create; the artist became a man in love. Though the chronology of the cues is different, the narrative resonates with the biography of Diego Rivera and Frida Kalho. An older artist attracted to a younger woman and clothing her to become a paradigm of the nation state or his idea of a model Madonna in a changing nation state. A whirlwind romance quickly culminated in marriage the following year. By then, the Catholic girl from Kirkee parish had shed her dresses under the tutelage of her mentor-husband and acquired a new persona wearing a sari and a mangalsutra. The artist had found a new muse.

Yessonda was born several years later in 1957. The artist was 55-years-old and Ivy was 31. The girl child was named Delfina after the artists’ mother, and Yessonda after a Dutch nun whom Fonseca had befriended. Yessonda Shrader became godmother to the little girl. Several paintings and sketches of Yessonda are found in the artist’s portfolio, some very personal and intimate, others mapping the vivacity of the growing child captured in soft, oil pastels with his hallmark white strokes. Soon these intimate etchings give way to a new public persona as the little girl whom he nicknamed ‘Chicken’ because of her low birth-weight became the stand-in model for his portrayal of the young Jesus.

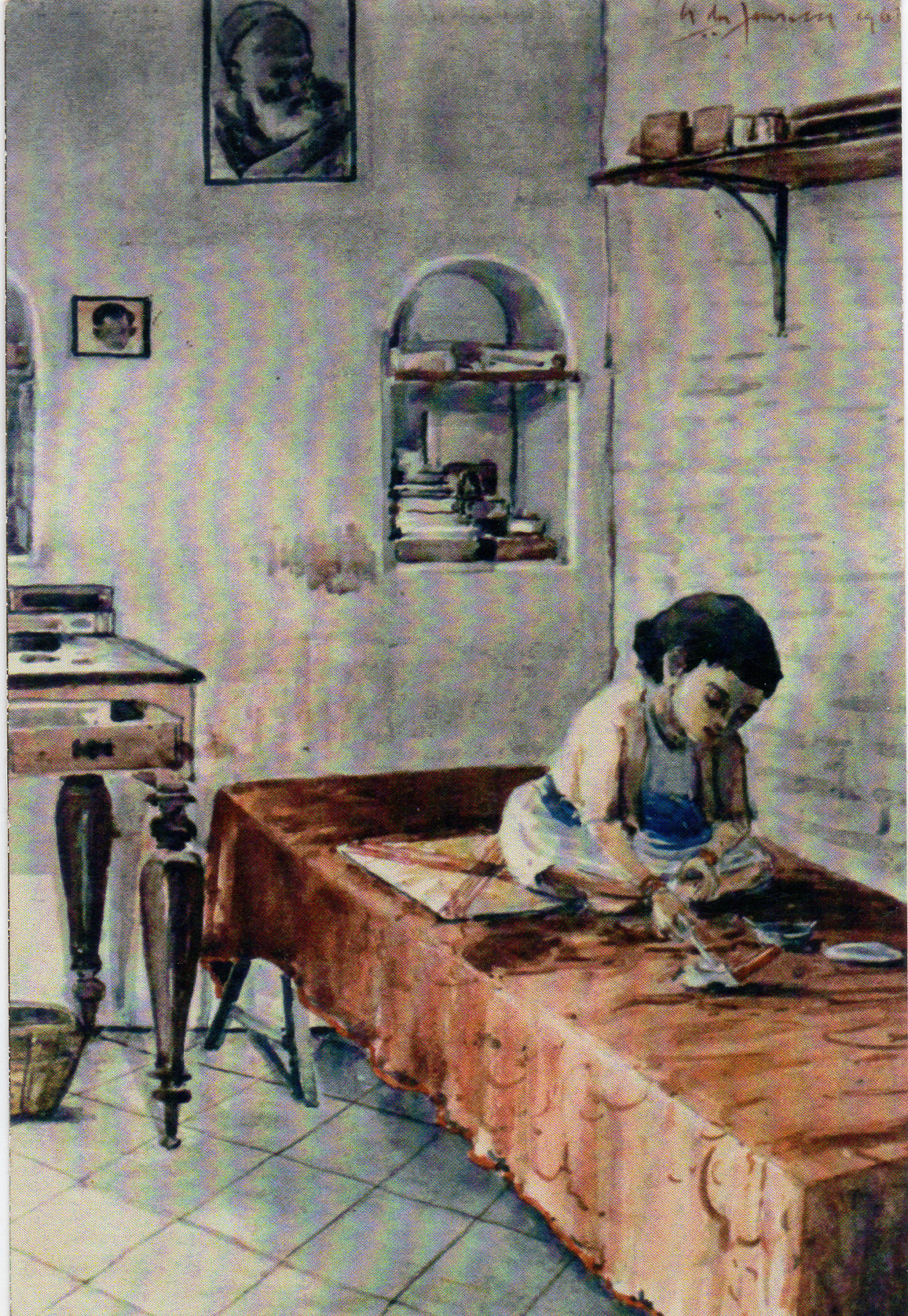

When Yessonda began school at St Anne’s, Fonseca picked her up after school hours. Her mother’s teaching responsibilities necessitated that she spend long hours away from home. Her father would take her to the Christi Purana Sewa Ashram where he had a cell-cum-studio. He set her up with crayons while he worked. One of his paintings depict the toddler with some crayons on his cell cot. The paintings offer, in the backdrop, a good study of how the cells were at the time. At home or at the CPS Ashram there were always spare crayons and paper for her to doodle with. Ivy showed me several pages of her doodles. Yessonda recalls his painting materials neatly arrayed on the window-sill by the dining table of their modest home in Arsenne Lodge Cottage on Irwin Road.

A relative confided, that Delfina, the artists mother would hand-create post-cards, it was part of the attitude of thrift and frugality endemic to all elite feudal families. This habit continued through the next generation. The Fonseca siblings communicated to each other through post-cards. As a child Yessonda remembers the sepia-tinted cards falling in through the postal-niche in their Poona home signaling the onset of vacations. Goa visit plans were mapped for November-December or May and sojourns mapped out. ‘Plop, plop, plop, the postcards would fall,’ she recalls.

The young Yessonda, as a student of St Anne’s School wondered why her father was an old man. ‘I would observe other parents, young and compatible in age and make constant demands on my father. Most parents were trendy. I would constantly tell my daddy to dress like the other parents. The year he died he stitched a new suit to please me.’ She remembers.

Fonseca died at the pinnacle of his artistic career. The third and mature phase of his work had taken off setting bold compositional flows in his work. His own distinctive style had reached maturity wherein the amalgamation of eastern and western imagery flowered a new dynamic. A pantheon of Christian iconography emerged as his signature. Some compositions were dark and a little bold, no doubt, contrasting against the established canon. Nonetheless it was arresting in its newness, and its rich vocabulary of meanings. The artist always painted with Windsor and Newton paints whether it was oils, gouache or watercolours. He blended these with some of his home-ground colours, pounded from rocks and clay. These tints bonded with Windsor and Newton Gum Arabic, to create new shades of terra-verte and grey used as background or dominant colour palettes for several of his paintings.

‘In the late fifties, a French teacher and artist doing a residency in Poona gifted him a huge packet of handmade paper. Colours changed, so did his imagery. Daddy was a morning person. All his paintings were worked on in the morning light.’

We had arrived on the road where the Fonseca family home was located. The artist’s visits to Santo Estevam were few and far between for the artist preferred to spend time with his sisters in Chicalim, Utorda and Chinchinim or with Alice in Carmona rather than live in the old manorial mansion. No trace of its grandeur remains today except in a clutch of Fonseca paintings. Only rubble and old laterite stones beneath fallen leaves of mango, breadfruit, sal and oak whisper the old story of derelict neglect and collapse. Houses like people live as long as they are wont to.

Yessonda navigated a small flight of stairs and proceeded to an oddly shaped structure. ‘This well,’ she says, ‘could be accessed from the upper floor. A flight of steps led to a very ornately carved cupboard, a camouflaged trap that opened on to the well. It was built to deceive thieves and Rane brigands.’

Square plots were created Fonseca’s nephew Dr Lousito da Fonseca after the old house collapsed. These plots demarcated with old stones now hold a scatter of new houses that have come up in the area where once the old mansion stood. We took the lane from which emanated the smell of freshly baked bread. Dominic opened the door of the bakery and let us in. Dominic’s father tenanted the back shops to start a bakery. Originally from Betalbatim he migrated north as part of a wave of migrants from the south who moved residences to provide services to the newly emerging Pangim city across the river.

Having grown up here, Dominic opens a cache of memories of the house, its stately rooms, its bhuir- the underground tunnel which opened up in the garden and led to a safe haven in case there was a siege on the house. The well in the courtyard had a primitive irrigation system which would release water into a pond located in the vicinity where fresh fish was farmed and was a novelty of sorts on the island village.

Some parts of the village where old houses still exist are peaceful and verdant. We knock on the church door prompted by a rumour that it houses a Fonseca painting. The main portal bears icons carved into the wood in the manner of St Braz church in old Goa. The door is opened by a woman chaplain. The artist’s early influence the adorn white-washed walls: the station of the cross series in European style academic art, life-size alabaster statues of St Antonio and Sant Domingo perhaps of Indo-European Christianity or imported from Italy or Spain.

‘Like many artists prone to depression, he was creative for long periods but without any output at other times.’ The chronological dateline of his oeuvre bears tell-tale signs of manic spurts of energy with a massive output of paintings and then phases where he does not paint at all. The same year, that I met him he visited Alice’s home in early December, troubled and restless which the extended family noted as an artists’ angst. Antonio Pereira recalls the artists’ conversations with his mother, Alice on that visit. His fears that he may not live to see his daughter grow into adulthood had begun to oppress him. Yessonda was 10 when Fonseca died on December 28, 1967, far too young even to comprehend the loss or the legacy of her father.

Past the cemetery, we cross seamless water-bodies, presumably arms of the river Mandovi in whose tentaclutch the island nestles. At the ferry-point, at Santo Estevam, the chug of the old contraption has ceased. A huge rust-coloured barge, three storeys tall parts the waters and sails by, its gargantuan body casting a shadow. I turn my eyes away to look into the mangroves whose turgid waters, dark yet shimmering with the light of a few sunbeams suddenly reveal an empty vhoddem anchored amid the water-plants. The oar rests as the ripples rock it gently.

The Blind Oarsman by Angelo da Fonseca, 1967.

The shadow of the barge, the tonality of light in the mangroves conjure up a fleeting mirage of one of Fonseca’s last works The Blind Oarsman. Paddling in his wind-tossed vhoddem, laden with the day’s catch, on the waters with his little child at the other end. The oarsman looks towards infinity with sightless eyes as the waves and seagulls thrash his doomed vhoddem. It was a dark painting executed in 1967, a little before he died.

The barge has passed, and the illusion slowly fades.

The banner picture is of Angelo, Ivy and Yessonda, the Fonseca family c. 1967. Picture courtesy of Fonseca family

Savia Viegas is an artist, art historian, art curator, and writer. She holds a PhD in art history and has taught at the University of Mumbai. A former Senior Fulbright and Ministry of Culture (India) Fellow, she is the author of several books including Let me tell you about Quinta (Penguin, 2011). Her latest book is the graphic novel, Song Sung Blue (2019).