By Selma Carvalho

As a child, I might have visited Miguel Colaco’s Christ Ashram in Nuvem. It was after all, within walking distance from the Mae Dos Pobros Church, and it was not at all unusual for Catholics in Nuvem, after mass, to drop in at the ashram. I have a recollection of a blue sky, people crawling on all fours, sweeping the earth with their hair, and supplicating in other grotesque parodies of faith. These memories are almost certainly false. They have been created in my mind by the many stories told to me, for the ashram and its paradoxes were an enigma and a constant talking point in the village of Nuvem.

Robert S. Newman, the American anthropologist, who has spent many years studying Goa in its various transformations, has recently released two volumes of his anthropological papers, which delve into aspects of Goa’s mythologies. Newman is a much respected academic, who first visited India in the 1960s, as part of the American Peace Corps, when still in the bloom of Kennedy-era idealism, Americans sought to engage with the world through learning new cultures. In the volume titled, Goan Anthropology: Festivals, Films and Fish (Goa 1556, 2019), Newman now fills the gaps in my porous memory about Christ Ashram.

The genesis of Christ Ashram is shrouded in mystery. Newman, however, narrates the two stories told to him. In the 1960s, a boy found a cross in the vicinity of Nuvem and handed it to Miguel Colaco, who took this to be a sign, a calling, to heal. The other story is, Miguel Colaco, poor, illiterate, and of subaltern caste, used to work in the Bicholim mines, whereupon he came across a cross and embraced his mission as a healer. Both stories are likely to be apocryphal, for healers, seers and mystics with similar stories abound in shasti Goa, particularly where the boundaries blur between adivasi, Hindu and Catholic populations. This in itself, is evidence of the syncretic nature of Goan Catholicism, and the widespread (although discreet) popularity of shamanistic cults, which Newman firmly posits as a variant of bhakti, the path of faith and devotion more visceral than scriptural religions.

Christ Ashram is rooted in the traditions of gariponn (in the local dialect, this is pronounced as gaddi), sorcerers capable of performing exorcisms, casting spells, divining futures, healing illness and comforting people against the vagaries of life. Newman is candid in his observations, when he writes, ‘the clientele or the devotees of Christ Ashram is overwhelmingly lower class. They are poor – small farmers or fishermen, labourers, sailors and their wives.’ The masses are seduced by spectacle, by miracles, by the courtship between magic and mortality, the ability of shamans to understand their everyday angst and provide pragmatic solutions. Newman explains: if ‘a special prayer session [ is conducted] just for you, to intercede with Jesus on your behalf, then you are getting help. Your problems are diagnosed, and a simple remedy is prescribed. Most devotees cannot afford extended medical treatment.’

Some years after Colaco began his ‘ministry’, he was joined by Eugenio Gonsalves, who had spent time at Pilar Seminary albeit unsuccessfully. Gonsalves fused more traditional elements of Catholicism – devotional hymns and prayers and its classic iconography, to Colaco’s mysticism, to present Goans with, what can best be described as an irreligious religion. It is perhaps not a surprise that syncretic religions flourish where indigenous beliefs are strong and able to permeate superimposed cultures. Hence they are most visible in Latin America, Africa and Melanesia. This syncretisation process ensures a unity of identity despite an apparent diversity of faiths.

Newman is by no means condescending of those who visit the ashram. He seeks only to understand the fictive abstractions underlying the pan-India consciousness. Long before Yuval N. Harari in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Penguin, 2011) popularised the idea that the human ability to create fictions was fundamental to evolution, Newman sought to understand a pan-India consciousness, not solely through its collective thought-process but the commonality of ‘feeling.’ He writes: ‘I am interested in the relationship between image, imagination and world view. A world of unconscious perception underlies the way people seek answers about Life and Reality.’

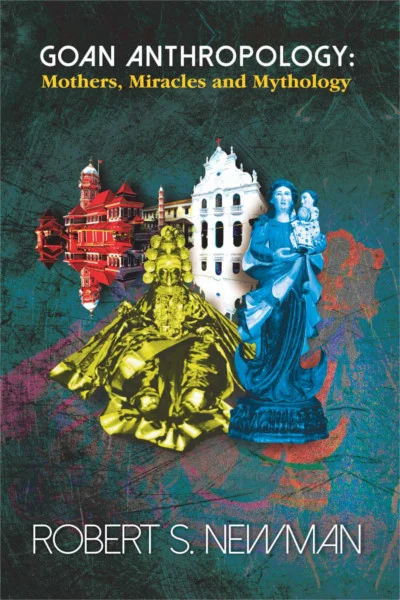

Much of Newman’s anthropological work in and around Goa, focuses on its mythologies, and their ability to subsume the old into the new. The volume titled, Goan Anthropology: Mothers, Miracles and Mythology, covers Indian Mother Goddesses in their new avatars as Christian deities, cross-over festivals in Cuncolim and unlikely prophets in Velim, expounding the theory that by such means the powerless assume power in Goan society.

Newman conducted his field work between 1970-1990. If he were to return to Goa today, with a view to revisiting this topic, he might be mildly surprised to find that, while gariponn has all but receded from public consciousness, (Christ ashram has faded into obscurity, despite Eugenio’s efforts), it has been replaced by another form of spectacle – American-styled evangelical Christianity. This wave of proselyting and worship is not discriminatory, it has successfully brought under its fold all classes of Catholics, but predominantly its educated middle-class.

In this rousing evangelisation, there is no resistance at all to the immorality of the charlatan, the crook, the trickster with his smoke and mirrors, bleeding crucifixes, and weeping Madonnas. Rather, the false prophet is revered; he is all-powerful, capable of curing all the ills of society. Goans have been reduced to infants, to crude servility, with no interest in assuming responsibility for their lives. Alcoholism and gambling can be blamed on the devil, cancer and diabetes, can be blamed on the evil eye. Exorcisms are conducted, where people consumed by guilt succumb to auto-suggestion, convinced that the devil is fleeing their body. Mumbled tongues are said to heal wasting muscles and afflicted minds.

This is the worst intellectual corruption and evolutionary regression, Goa is witnessing since Liberation; this sort of religion can never produce the wondrous painter, the brilliant architect, the literary doyen, the virtuoso musician, the radical thinker or the progressive reformer. The clientele of this new religion is the conformist, the collectivist coward, and the regressive malcontent of the 21st century.

Perhaps, in the end, our ancestral past is never too far away from our modern present. What lives on in all of us is a desire to manipulate our destines through the Divine. The gloss of the fictive dream is the many names it assumes, but deep down it is always the same. To be a perpetual child, to find a saviour and be saved.

Robert S. Newman is an anthropologist based in Massachusetts, America, primarily known for his research on post-colonial Goa. He first visited Goa in the 1960s as a volunteer with the American Peace Corp. The two volumes of Goan Anthropology spanning several decades of notes and papers, can be purchased here.